Nantes Passage E1

Since the late 15th century many of the houses situated around the area of Spital Fields had been occupied by Flemish protestant weavers. They had built up a reputation for fine quality products and a century later the number of workers in the trade had increased multifold. An order proclaimed by the French authorities in 1598 – the Edict of Nantes – gave religious freedom to French protestants, known as Huguenots. Its revocation in 1688 caused thousands of refugee Huguenot silk weavers to leave France and set up their workshops near to the Spital Fields. By the early 1700’s the number of weavers employed was over 30,000 and it is estimated that there were some 15,000 looms in operation. The weavers adopted as their spokesman and campaigner, a local landowner by the name of George Wheler. Having recently returned from France, he understood the lives of the Huguenots, showed sympathy to their needs and built them a small chapel on the site of this Passage. It was the first of twelve places of worship built over the following years for the sole use of the silk weavers.

As fashions changed and cheap imitations were imported from the Continent the prosperity of Spitalfields went into decline, forcing workers and their families to move to cheaper housing. Further gloom hung over their heads as technical advances lead to automation in the weaving industry, spelling out very clearly the numbered days of the handloom. Steadily the French population decreased. One by one the chapels were sold off or demolished and by the beginning of the 19th century there were over 40,000 silk weavers without any form of work. The last of the chapels, on the corner of Fournier Street and Brick Lane was taken over by the Wesleyan congregation, and in 1899 it was modified as a synagogue to serve the increasing Jewish community.

All of this area is in the midst of long-lasting suspense-pending finalisation of building plans. Spitalfields Market has removed to another site, the adjacent Flower Market too has been vacated and the Market Garage, on the west side of the Passage, is broken and adorned with graffiti. It is also of worthy note that Nantes Passage is of over-sized proportions in relation to its width and is in no way representative of our image of a typical City passage.

Neal’s Yard WC2

UG: Covent Garden

Bus: 6 9 11 13 15 23 24 29 77A 91 176

From Covent Garden Station, cross Long Acre and turn into Neal Street. Cross Shelton Street and Earlham Street then turn left into Shorts Gardens. Neal’s Yard is then on the right.

The Yard is attributed to Thomas Neal, associate of Nicholas Barbon, one time Master of the Mint, and Groom Porter to Charles II. Both Neal and Barbon shared similar obscure principles in relation to their business methods. They attracted investment on the strength of their speculative propositions but usually came unstuck through poor management. Neal was responsible for the construction in 1693 of the converging roads known as Seven Dials where Monmouth Street cuts through the central hub and five minor roads radiate out like spokes of a wheel. Its naming reflects not the layout of the roads themselves, but the seven sundials mounted on a central column – one facing each street. Although the diarist John Evelyn enthused over the design ‘where seven streets make a star from a Doric pillar placed in the middle of a circular area…’, had it been left to some of his fellow citizens the place might have been called ‘seven trials’. The column was removed in 1773 to Weybridge Green in Surrey and placed there as a memorial to the Duchess of York.

Neither of the access openings to Neal’s Yard can be regarded as enterprising advertisements. From Shorts Gardens the way is as an uncared-for entry, whilst the square covered entrance from Monmouth Street is almost a deterant to the wanderer unfamiliar with this quarter. But any discouragement must be set aside, for this is a fascinating place where most of the array of small shops occupy old warehouse buildings of rugged brick. Neal’s Yard is absolutely brimming with tiny eating houses, many of them situated in the triangular section about half way along, where there are always a good many people milling around. Next-door-but-one to Neal’s Yard, in Shorts Gardens, is Neal’s Yard Dairy, the most complete cheese shop of all time, its shelves sagging under the weight of well matured whole cheeses – a must for all lovers of cheese.

Nelson Passage EC1

UG: Old Street

Bus: 43 214

From Old Street Station turn into City Road (going north). Keep to the left and cross Baldwin Street, Peerless Street. Pass Moorfields Eye Hospital. Cross Caton Street and Bath Street. In about 75 yds turn left into Mora Street. Nelson Passage is just on the right.

London boasts many memorials to Viscount Haratio Nelson. The most obvious is, of course, the very well known column towering 170 feet high in Trafalgar Square, erected to celebrate his victory at Trafalgar. There are other tablets and plaques scattered about the City; a statue of the’modern’ admiral in Deptford Town Hall, the memorial stone over his final resting place, a monument in St Paul’s Cathedral, and in some way, Cleopatra’s Needle on the Victoria Embankment. The 3,500 year old column was offered to England in 1867 after Nelson came through victorious in the Battle of the Nile, and after it had stood outside the palace of Cleopatra for 15 centuries.

Nelson Passage is perhaps not so readily attributed to the old sea dog but it was named as a tribute to the Admiral, who succeeded at Trafalgar in 1805. There are no monuments or relics on view here; on the contrary, it can be quite plainly and truthfully stated that the most notable feature of this narrow walk-way is a solitary characterless stump at the Mora Street access. Dirty high walls on one side and a complimentary wire-netting fence on the other are the adequate descriptive syllables required to paint a detailed picture of this insalubrious little cut-through. However, do not despair; the rather more welcoming atmosphere of the Nelson public house in Mora Street will help to gladden the heart and perhaps prepare your spirits for the equally depressing experience of Guinness Court, across Lever Street.

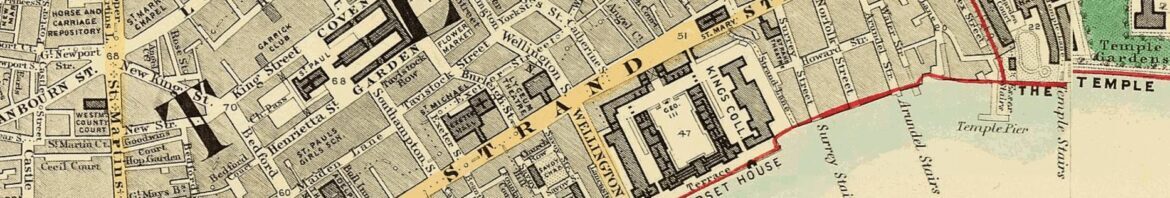

New Inn Passage WC2

UG: Holborn

Bus: Any to Aldwych

Off the north side of Aldwych, between Kingsway and the Law Courts, turn into Haughton Street. New Inn Passage is about 20 yds on the right.

Until the beginning of the 20th century New Inn was one of the Inns of Chancery, so named because it was newer than Clement’s Inn. The main entrance to the Inn was from Wych Street, now non-existent, with New Inn Passage providing access to the rear. Clement’s Inn and New Inn both shared common relationships, they were regarded as the creme de la creme and attracted the more respectable element of the largely questionable legal profession. There were gardens of tree lined walks adjoining the Inn where members of both societies – Clement’s and New – mingled in recreation. So closely situated were the two inns that until 1723, when a gate and railings were erected, there was little to distinguish the division. In 1486 the members of New Inn leased from Sir John Fincox, Lord Chief Justice of the King’s Bench, a travellers hostel known as ‘Our Ladye Inn’. This they turn into New Inn Hall and for the convenience they paid a rent of six pounds per year – ‘for more (as is said) cannot be gotten of them, and much lesse will they be put from it.’ One of the most notable members of New Inn was Sir Thomas More, Chancellor to Henry VIII.

In 1900 work commenced on the construction of Aldwych, Kingsway, and the widening of the Strand and as a result of the proposed plans New Inn was disbanded and demolished in 1903. Along with it also went Wych Street, Holywell Street, known as Bookseller’s Row, and a whole host of alley’s and passages. High rise buildings are the only present day feature of this remaining short cul-de-sac.

Newcastle Court EC4

UG: Mansion House

Bus: 4 11 15 17 23 26 76 172

From Mansion House Station (Cannon Street south side) walk east for about 70 yds and turn right into Queen Street. In about 20 yds turn left into Cloak Lane and take the first right into College Hill. Newcastle Court is a few yds on the right.

Here is one of those typical City crannies, so unperceived that if you stand at its entrance and ask directions of passers by, you will scarcely find one in every dozen who will be able to tell you. Enquire into the origin and you may well be there all day without learning anything of significance. The name is a misleading error made over a century ago by a sign maker joining the two words ‘new’ and ‘castle’. It has no connection whatsoever with that coal producing town in the northeast and neither does it have any associations with a suburb of Stoke-on-Trent.

When London was recovering from the devastation left by the Great Fire, Lord Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, took up an offer of a piece of land on the west side of College Hill and erected ‘a very large and graceful building’. The Villiers family already held a large estate on the south side of the Strand but this was to be His Lordship’s business address ‘for the more security of his trade, and convenience of driving it among the Londoners.’ He had an astute mind for business matters, introducing new ideas with an explosion of enthusiasm, but his morals were too frequently laxed, leading to failure after failure. John Dryden once summed up the strength of his commercial activities thus: he was ‘everything by starts and nothing long.’

By the end of the 17th century the Duke had abandoned his ‘business address’ and the house was occupied by Sir John Lethieullier, alderman of the City and elected sheriff in 1674. The house was demolished about 1730 and small merchants’ houses, collectively known as Castle’s New Court, were built on the site. Over the following years these houses gave way to office buildings, and successive development of the area has seen the gradual elimination of the grand courtyard. In the name of Newcastle Court one small part still remains, now merely a passage leading to a yard dwarfed and squeezed amid its modern neighbours. There is little point in planning a stroll through the Duke’s old stomping ground at weekends – it is gated and padlocked.

Almost opposite, on the east side of College Hill is the church of St Michael, Paternoster Royal. It stands on the ground that has supported a church since about 1220, and first recorded in the Calendar of Wills of 1259 as ‘Paternoster cherch’ and in 1301 it is mentioned as ‘Paternoster cherche near la Rayole’. Paternoster is derived from the pre 17th century name of the lane – Paternoster Lane, the habitat of the rosary makers. ‘Royal’ comes from the 12th century settlement of wine merchants who imported their stock from the vineyards of Reole, Bordeaux -the area to the northern end of College Hill became known as ‘the Reole’, (see Tower Royal).

Newman Passage W1

UG: Goodge Street

Bus: 10 24 29 73 134

From Goodge Street Station turn into Goodge Street and on the left cross Whitefield Street, Charlotte Street and Charlotte Place, then turn left into Newman Street. Newman Passage is about 140 yds on the left.

Leaving Newman Street through a square covered tunnel beneath the premises of ‘Decorative Lighting’, Newman Passage gives rise to expectations of interesting features. Although it is, in its own way, an attractive Passage, with a fine cobbled footway, the mindful anticipation is soon thwarted, and further along we turn at right angles in breathless preparation for the unexpected surprises that so often greet us around such corners. But no, it has to be revealed that there are none. Unfortunately, this one-time cut through is now a passage to nowhere; truncated by the establishment of the Post Office vehicle depot in Newman Street.

As part of the Berners estate, Newman Passage has witnessed a long history reaching back to the 1740’s when William Berners started to develop Newlands Field, purchased by his father, Josias Berners, in 1654. First to be built was a narrow track leading north to the Middlesex Hospital but it was not until the 1760’s that this road was widened and named Berners Street. Newman Street and the tributary Passage came along in 1746, built up with fine houses on either side. The naming of Newman Street and Passage is not a matter of absolute clarity. One possible clue is a corruption of Newlands (Fields) but some turn their sights on the fields to the north in search of the answer, resting on the conjecture that the Berners family owned Newman Hall, a few miles south of Saffron Walden in Essex.

Newman’s Court EC3

UG: Bank

Bus: Any to the Bank

Newman’s Court is off the north side of Cornhill about 165 yds east of Bank Station and just east of Finch Lane.

Here in the heart of the financial City, opposite the towering spire of St Michael’s, Cornhill, is the little covered alley where Mr Newman and his family set up home in 1650. His move to Cornhill was far from plain sailing – the house he had set his sights on was the property of the Merchant Taylors and the alley was the Company’s right of way to their Hall. Naturally, the Taylor’s wanted to maintain their access and offered Newman a lease on that understanding. Newman moved into the house on a verbal agreement to the Company’s terms but later, when he became tired of the constantly parading feet, had second thoughts and tried to bar them from using the alley. He might have been in a position to negotiate more favourable terms if it had not been for his bull-at-a-gate approach; an almighty argument exploded and the Company of Taylors threatened him with eviction if he did not comply with their request. Such was the influential power of the Company that Newman may have been prevented from securing any other property on his eviction. He realised this and without any further ado succumbed to their terms.

In the many changes that Cornhill has seen over the centuries and in this heyday of modern development when concrete frames filled with plate glass are shooting forever skyward, it is amazing how this Court and numerous others have survived. Old Newman would hardly recognise it now, with cars of Midland Bank employees parked where his house once stood. But, along with his descendants, he would probably be over-joyed to find it here at all.

Newport Court WC2

UG: Leicester Square

Bus: 14 19 24 29 38 176

Off the west side of Charing Cross Road, about 35 yds north of Leicester Square Station.

This area has long been associated with shops and retailers stalls, for here was the extensive Newport Market, curtailed when Charing Cross Road was extended southward in 1887. It was in this market that politician Horne Tooke, when in his youth, helped out at his father’s poultry shop. Horne never lived it down when his chums at Eton asked what his father did. ‘A turkey merchant.’ he replied.

Many of the courts in the Charing Cross Road area are typically shopping thoroughfares, some with little cafes, and the occasional pub. They were, of course, not originally built for the purpose of retailing, but most private dwellings were turned into shops in the late 1800’s when the area became a traders paradise. Of particular note in Newport Court are numbers 21 to 24, a row of 17th century buildings converted, as seemed to be the trend, in Victorian times. They were built by the property developer Nicholas Barbon (see Crane Court) on the site of Newport House which he purchased from George, Earl of Newport, in 1682.

Newport Court is a notably different court – nearly all the shops are Chinese. On the corner of Newport Place there is a Chinese supermarket with stalls outside displaying exotic fruits and vegetables. Further along is a tiny cafe advertising ham and egg buns and sausage buns, there is a travel agents, book shop, Chinese Tourist Information Centre, a jeweller, and many others. If you want to sample real Chinese food, this is the place to come, as long as you don’t mind being the only none Chinese person eating. Even the Court name board bears the Chinese translation.

Northumberland Alley EC3

UG: Aldgate

Bus: 5 25 40 42 78 100 253

Follow directions for Back Alley

‘Then a lane that leadeth down by Northumberland house towards the Crossed friars…’ When John Stow wrote this in 1598 the Earl, Henry Percy, had already taken his leave of the mansion and moved to pastures new further west. By this time the grounds of the great house had been converted into bowling alleys, and the house itself had become a den of gambling and vice ‘common to all comers for their money, there to bowle and hazard.’ Unfortunate for the management, illegal gaming houses were springing up all over London and the punters only came in a trickle. The venture never got off the ground and within a short time the house was turned into tenements and the out buildings were prepared as cottages, all to accommodate the homeless and foreigners.

A little way into the Alley, Carlisle Avenue leads off to link with Jewry Street but its history seems firmly secured in the depths of time. Further along is Rangoon Street where the innumerable tea warehouses of the East India Company once dominated the scene. That Company was dissolved in 1861 and the East India Dock Company took control, but with the demise of shipping on the Thames and the eventual closure of the docks they too folded in 1969.

Between two City of London crested bollards the Alley descends from Fenchurch Street amid buildings old and new towards its southern extremity in Crutched Friars. As a general view of the scenery in Northumberland Alley there are few glaring spectacles to raise the eyelids that extra millimetre. In fact it is a very general sort of place, until, that is, we home in on the Hall of the Worshipful Company of Gardeners where they have created a picture of sheer delight. The central feature of this small private garden is a miniature Niagara sending a cascade of water crashing into the pool below, accompanied by dancing fountains. A rewarding highlight in this otherwise characterless byway.

In 1785 there was a discovery in the Alley of several Roman paving stones, now in the keeping of the Society of Antiquaries.

Nottingham Court WC2

UG: Covent Garden

Bus: 6 9 11 13 15 23 24 29 77A 176

From Covent Garden Station cross Long Acre and turn into Neal Street. In about 90 yds turn right into Shelton Street. Nottingham Court is a few yards on the left.

For the origin of Nottingham Court we must look back to the second half of the 17th century when Heneage Finch, first Earl of Nottingham had a house in Great Queen Street. A lawyer of the Inner Temple, Finch moved into the parish of St Giles-in-the-Fields when Great Queen Street was still in its primary years. The area was, however, already fashionable with wealthy families wishing to rub shoulders with James I after he had taken a shine to Theobolds House and made this his principle private route from Westminster. When the developers moved in and erected some of the most sumptuous houses in London, the presence of Heneage Finch, no doubt, enhanced the attraction. He was an influential Tory and in 1660 became Solicitor General, Lord Keeper in 1673, and two years later was appointed to the office of Lord Chancellor.

Nottingham Court was named to his memory, but as honourable as he was, his father was the driving force behind his success. Serjeant Finch, Recorder of London and Speaker of the House of Commons, descended from a long line of political and legal ancestors. He owned Nottingham House in Kensington, which was sold by his grandson, Daniel, in 1689 to William and Mary, and thus became Kensington Palace. It remained the principal residence of the reigning sovereign until the death of George II in 1760.

If Heneage Finch could see his memorial court today he surely would not be at all pleased to have it associated with his name. There is a most suitable and well-understood expression to describe this place; it has no flowery syllables or tongue-twisting pronunciation; it is quite simply – grubby. Whereas nearby Broad Court has neatly positioned potted shrubbery about its friendly old stone slab paving, Nottingham Court untidily exhibits industrial refuge disposal bins about its broken Tarmac paving. In this overwhelming immediate environment one feels a sort of pity for the Covent Garden Christian Centre – The London City Mission who have their premises here.

At the southern end of Nottingham Court is Shelton Street, commemorating William Shelton, a wealthy trader, who left provision in his will of 1672 to build a school for under privileged children. Shelton was a charitable man; he could not pass a pauper by without offering some good deed; money to buy food or an article of clothing. His will named executors to take charge of a sufficient sum of money to purchase clothing for twenty aged poor people each year.

At its northern end the Court emerges into Shorts Gardens, where, until the end of the 17th century, William Short caringly tended his plot of land and grew plants for the gardens of Gray’s Inn, where he filled in his time digging and hoeing.

Nun Court EC2

UG: Moorgate

Bus: 172 to Moorgate

21 43 X43 76 133 141 172 214 271 to London Wall

From Moorgate Station walk south along the west side of Moorgate. Cross to the south side of London Wall and turn right. In about 45 yds turn left into Coleman Street. Nun Court is about 75 yds on the left.

As tempting as it might be to hallucinate the one-time presence of a nunnery on this site, there is no evidence in support of any such claim. It must therefore be assumed that the Court acquired its name from either the builder or an influential resident. John Stow remarked of Coleman Street, ‘This is a fair and large street, on both sides built with divers fair houses, besides alleys, with small tenements in great number.’ He wrote this in 1598 and had he returned to the street eighty years later he would have reported a very similar picture. Coleman Street was tightly packed with houses in those days and likewise, the alleys and courts leading off were almost bursting at the seams. There were no less than six houses along each side of Nun Court and at the far end was a large house with a rear garden which could have been built for Mr Nun himself. Of course, Moorgate, to the east, was not constructed at that time and so the Court would have been considerably longer than it appears today. All the houses in Nun Court have long since disappeared and in the short cul-de-sac there is but a single access door.

The alleyways and courtyards of London

This page is taken from Ivor Hoole’s defunct GeoCities site listing the alleys and courtyards in Central London, last updated in 2004 and now taken offline.

The Underground Map blog lists this information as is, with no claim of copyright.