| Kensal New Town | Notting Hill in Bygone Days by Florence Gladstone |

Table of contents |

The Borough of Kensington is divided into nine Wards, five of which are on the south of Uxbridge Road, and four on the north of that road. Of the four northern wards Norland Ward and Pembridge Ward lie between Uxbridge Road and the curved line of Lancaster Road ; they are divided by Ladbroke Grove. Golborne Ward, a comparatively small area to the east of Portobello Road, includes Kensal Town, and was dealt with in the preceding chapter.

St. Charles’s Ward, the remaining tract of land, is much larger than any of the others. It is bounded on the east by Portobello Road, on the north by Harrow Road from Ladbroke Grove to the western limit of Kensal Green Cemetery, and on the west by the parish boundary as far south as Lancaster Road. When Mr. Loftie wrote of Kensington in 1888 ” a new quarter ” was ” rapidly springing up on the slope towards Kensal Green,” and ” New Found Out ” was a local name given to the district. But, although this ” quarter ” is of recent growth, some of the earliest associations of Notting Hill fall within St. Charles’s Ward. The Manor House and farmstead of Notting Barns, surrounded by wide-spreading pastures, was in the valley to the north of Notting Wood, and on ” the way from London to Harrow ” a few small houses, some in Kensington, some in Willesden parish, formed the picturesque hamlet of Kensal or Kellsall Greene. Up to quite recent times this part of Harrow Road was little more than a country lane. It is reported to have been the scene of some of Dick Turpin’s exploits.

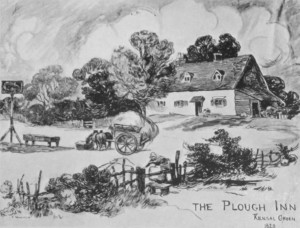

In Cary’s Plan of London, 1810, it is only marked by a dotted line, but from the sixteenth century onwards the ” Plough ” with its oak timbers and joists had stood beside this track.

In Cary’s Plan of London, 1810, it is only marked by a dotted line, but from the sixteenth century onwards the ” Plough ” with its oak timbers and joists had stood beside this track.

According to Faulkner ” Morland the celebrated painter was much pleased with this sequestered place, and spent much of his time in this house towards the close of his life ; surrounded by those rustic scenes which his pencil has so faithfully and ably delineated.” George Morland was born in 1763 and died in 1804.

In the year 1786 he married Nancy Ward ; her brother William Ward, the engraver, marrying Morland’s sister.

The Morlands lived in Kensal Green until after the death of their little son. The well-known picture of “Children Nutting” was engraved in 1788, two years after this marriage. It seems quite possible that the subject was suggested by the nut-bushes which, according to tradition, were plentiful all over the neighbourhood.

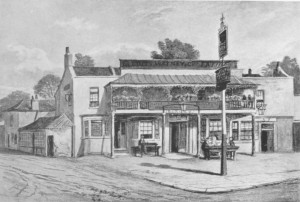

The ” Plough ” at an earlier period has already figured in Chapters I and II. It was still very countrified even in 1868, as is seen from the second drawing here. No signs of rustic beauty remain in the present large brick building at the corner of Ladbroke Grove and Harrow Road, but it must be remembered that this is the only house in North Kensington that has a name dating back four hundred years.

A description of the district written by Mrs. Henley Jervis in 1884 is of special value. She states that before the nineteenth century this part of Kensington was ” an extent of woodlands, cornfields and heath, the heavy clay ground often becoming well-nigh impassable in rainy weather, as even the present generation can understand if they recollect Lancaster Road and Elgin Road in 1862. Tradition tells us that Prince George of Denmark (Queen Anne’s Consort) well-nigh came to grief by his horse becoming completely bemired somewhere near the present St. Charles’s Square.

The old Plough ‘ was the most distant dwelling in the north-west of Kensington parish ; upon the borders of the debatable land to which we (Kensington) Chelsea and Paddington have rights of so ill-defined a nature, that within the last three years the highway near the Canal Bridge was a grievance to man and beast, and it was no person’s business to mend it.”

Chapter I of these Chronicles shows how difficult it is to determine the limits of Kensington and Paddington in early days, so this reference to the continued vagueness of the boundary line is most interesting. Dr. Stukeley, the Antiquarian, in Notes written about 1760, speaks of Kelsing or Cansholt Green as belonging to the parishes of Paddington, Kensington, Chelsea and Willesden, and says that at Canshold Green on the road to Harrow ” the parish of Chelsea have erected two posts in this road showing how far they are to mend thereof “.

After the Perambulation of Kensington Parish in 1799 boundary posts were placed on the south side of Harrow Road. The ” Beating of the Bounds ” seems to have been carried out for the last time on Ascension Day 1884, but disputes about the division of the parishes continued until Kensal Town was definitely handed over to the care of the Borough of Kensington.

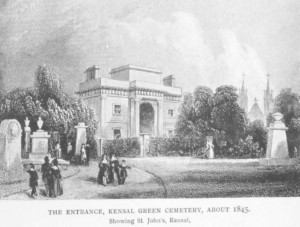

The first encroachment on this stretch of open land was the cutting of the Paddington Branch of the Grand Junction Canal, which was opened for water transport in 1801. Some thirty years later land lying between the canal and Harrow Road was converted into a burial ground.

Kensal Green Cemetery occupies the highest ground in North Kensington and reaches 150 feet above sea-level. The view from the terrace in front of the Cemetery church is still beautiful, and must have been far more beautiful in bygone days. The 56 acres of 1832 have been increased to 77 acres, and many of the most conspicuous personages of the Victorian Era rest in Kensal Green.

Kensal Green Cemetery occupies the highest ground in North Kensington and reaches 150 feet above sea-level. The view from the terrace in front of the Cemetery church is still beautiful, and must have been far more beautiful in bygone days. The 56 acres of 1832 have been increased to 77 acres, and many of the most conspicuous personages of the Victorian Era rest in Kensal Green.

Modern writers on the subject are apt to decry this ” forlorn necropolis,” ” the bleakest, dampest and most melancholy of all the burial grounds of London,” and to deplore the waste involved in its huge mausoleums and oceans of tombstones.

But the walks are lined with beautiful trees, and, as with other cemeteries near London, children haunt the place and get a grim satisfaction out of watching the interments. Besides this, on a summer Sunday afternoon, Kensal Green is largely visited by mourners and their friends ; thus to some extent taking the place of a Public Garden or Park.

The track of the Great Western Railway, running south of the canal, and opened for traffic in 1838, further curtailed the fields, and this curtailment increased with the widening of the line. Before 1850 (see map on page 120), the ground between the canal and the railway was taken over by the Western Gas Company, and certain buildings were put up.

A countrified house still stands within the boundary walls.

In the early eighties the premises were acquired by the Gas Light and Coke Company. The whole intervening space is now covered by their works, and the Sunday storage gasometer is one of the largest in London. Until the eighteen-seventies the canal and railway line were reached only by footpaths and were crossed by ferry or footbridge. All funerals approached the Cemetery along Harrow Road, the northern half of Ladbroke Grove being then unmade.

In the original copy of this photograph, dated 1866, hay-fields are seen beyond the railway arch, and, for several years after its construction, the embankment of the Hammersmith and City Railway was the limit of building in this direction. The first bridge at Notting Hill Station, now Ladbroke Grove Station, collapsed and had to be rebuilt. Gradually the road was pushed further and further north until it joined Portobello Lane and Wornington Road close to the bridge over the Great Western Railway, and thence proceeded along the old track to Harrow Road. This extension beyond the Hammersmith and City line was called Ladbroke Grove Road, and it is only in recent years that ” one of the finest streets in London ” has become known as Ladbroke Grove throughout its whole length.

Formerly a country inn occupied the position of the large corner house, the ” Admiral Blake,” close to the bridge over the Great Western Railway. Locally the “Admiral Blake ” is known as ” The Cowshed,” a reminiscence of the time when Admiral Mews was occupied by a series of sheds for cows. Drovers bringing their cattle to the London markets would house them in these sheds for the night, whilst they themselves found shelter and refreshment in the neighbouring tavern.

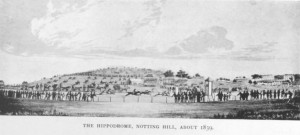

As stated in previous chapters, the building of the Hammersmith and City Railway forms a very important landmark in the development of North Kensington. Between Notting Hill Station and Latimer Road the line crossed the fan-shaped group of streets, bounded by Walmer Road, which Mr. James Whitchurch had planned in the middle forties. The land immediately to the north from Walmer Road to St. Quintin Avenue had been the extension of the Hippodrome grounds.

For some years after 1842, when the race-course came to an end, these fields were, apparently, still used for the training of horses, and were known as Notting Hill Hunting Grounds. It is said that, had the Chartist Rising of April 1848 been successful, the party leaders intended to encamp on these fields. No doubt the enclosure of this ground was the reason why building for many years did not extend beyond Walmer Road.

For some years after 1842, when the race-course came to an end, these fields were, apparently, still used for the training of horses, and were known as Notting Hill Hunting Grounds. It is said that, had the Chartist Rising of April 1848 been successful, the party leaders intended to encamp on these fields. No doubt the enclosure of this ground was the reason why building for many years did not extend beyond Walmer Road.

But in the sixties this land was laid out in market gardens, and terraces of small houses were built along the north end of Latymer Road. The three brothers Keen, John the dairyman, Joseph the market gardener, and Thomas the coal-merchant, had three houses on the site occupied since 1885 by Jubilee Hall. Opposite these houses, on the Hammersmith side of the road, stood the row of little dwellings forming Windsor Terrace, known locally as ” The Sixteens.” Each house had its pigsty and vegetable plot.

Latymer Road ended with the ” North Pole,” at this period a one-storied country inn. But the “North Pole,” was preceded by the ” Globe,” which probably dated from about 1839, when the Hippodrome grounds reached to this point. Globe Terrace recalls the name of this earlier inn, and the North Pole Road contains the modern tavern of that name. In later days this part of the Latimer Road district gained the name of Soapsuds Island.

The history of Notting Barns has been told up to the earlier years of the nineteenth century, when the larger portion of the old Manor was known as the Portobello Estate. But until 1860 the Notting Barn fields extended from Lancaster Road to the Great Western Railway, and probably covered 150 acres, the size of the estate in 1828. Before 1865 Colonel St. Quintin had bought the farm-house and the remaining portion of the Notting Barns land.

For many years it had been known as Salter’s Farm, and the farm land had been Salter’s Fields. Mr. Baldwin, who built houses on part of this land, employed an old carter who worked as a boy on Mr. Salter’s farm ” about Waterloo year.” If this statement is correct Salter must have rented the place while the name of William Smith, Esq., was still on the Rate Books. A Mr. Salter occupied the farm in 1873 ; he died shortly afterwards as a very old man at a house in Lancaster Road.

The drawing made in 1873 more closely represents Faulkner’s description of an ” ancient brick building surrounded by spacious barns and out-houses ” than does Henry Alken’s view of the house in 1841.

By 1873 the large barn was let to Mr. Leddiard, cowkeeper and dairyman of Ledbury Road. The man who attended to Mr. Leddiard’s cows lived in the cottage beside the barn. But Salter’s cows fed on fields further to the north, and were milked under a group of elms on land now covered by the Clement Talbot Motor Works in Barlby Road. The Salters must have been kindly folk, for Mr. Herbert Friend remembers having his head bound up at the farm after an accident with a toy cannon, and children were often allowed to clamber through the fence, and swing on a branch of the tree overhanging the pond. In winter this pond became quite a lake, and more than one child was near, drowned in it.

Between 1870 and 1873, on a Sunday afternoon, the late Lord Cozens Hardy and Mr. W. H. Gurney Salter used to enter the farm-yard by a five-barred gate, and emerge by another gate for a country walk. So rural were the surroundings that boughs of haw-thorn in blossom might be carried home from the site of Oxford Gardens, and violets are said to have grown where the ” Earl Percy ” tavern now stands. To go to Notting Barn Farm for a glass of milk became a recognized excursion; but about 1880 the dilapidated remains of the Manor House were pulled down. A French laundry, named Adelaide House, occupied the spot until about 1886, when it also had to make way for the encroaching building operations of St. Quintin’s Park. The farm-house stood where Bramley Road, if continued north, would have crossed Bassett and Chesterton Roads. For awhile the name was retained in Notting Barns Road. But, since that road became St. Helen’s Gardens, the old Manor which covered the whole district is only commemorated in the ” Notting Barn Tavern,” at the corner of Bramley and Silchester Roads.

For some years after the construction of the Hammersmith and City Railway, cricket fields lay to the north of the embankment. Here on one occasion the Notting Hill Flower Show and Home Improvement Society held its Exhibition, and the Duke and Duchess of Teck, accompanied by their young daughter, distributed the prizes. But in the middle seventies a series of good residential roads were planned running parallel with the railway, and as these roads were continued east across Ladbroke Grove Road, they linked up this district with the smaller houses of the Portobello Road area.

Naturally there is little of notoriety or public interest to record in connection with these somewhat ” featureless streets,” but pleasant vistas may be obtained along Cambridge and Oxford Gardens. and Bassett Road, with its avenue of plane trees, is often beautiful in the glow of sunset. The building of these streets commenced at Ladbroke Grove Road ; many years elapsed before their western ends were completed. (Most of these good detached houses are now divided into maisonettes or adapted into small flats.)

The plan of 1865 shows that building plots along the south end of Ladbroke Grove Road had been leased by Colonel St. Quintin to Charles H. Blake, Esq., who already owned much property on the top of St. John’s Hill. Mr. Blake must have acquired further plots along the road within the Portobello Estate, for, about the year 1870, Messrs. Blake and Parsons gave the site for St. Michael and All Angels. This church was built by Mr. Cowland (see pages 117 and 125), in terra cotta and ornamental brick in a style called ” Romanesque of the Rhine.” It was consecrated for worship in May 1871, and is, therefore, ten years older than Christ Church, Faraday Road. The first vicar was the Rev. Edward Ker Gray, formerly curate at St. Peter’s, Bayswater.

Mr. Gray lived with his parents in Linden Gardens. In 1871 his ministry was described as ” Evangelical in its character, and his services lively and devotional without ritualistic features.” But for many years the services at St. Michael’s have been adapted rather ” to those souls for whom an ornate worship is a necessity. ”

Rackham Street Hall, built by Mr. Allen, later known as St. Martin’s Mission, was long used as the Mission Church of St. Michael’s. Here the Rev. Henry Stapleton carried on good work from 1882 to 1889. (Since 1916, St. Martin’s has become a separate parish with a district stretching from Ladbroke Grove to St. Quintin’s Park Station.)

Shortly after St. Michael and All Angels was opened the freehold of eleven acres of Portobello Estate was obtained for St. Charles’s College, and by 1874 a handsome range of buildings in red brick and stone, with a central tower, 140 feet high, stood surrounded by a garden and recreation grounds. This college, dedicated to St. Charles of Borromeo, was founded by Cardinal Manning in order to provide education at a moderate cost for Catholic youths.

It began in 1863 in a room near St. Mary and the Angels, Bayswater. By 1890 twelve hundred students had been prepared for various professions. (Within the last few years the building has been sold to the Community of the Sacred Heart as a Training College for Women Teachers, and a small Practising School has been added.) The enclosure is faced on three sides by the houses of St. Charles’s Square. These houses at first were “inhabited by quite aristocratic people.” A convent belonging to the close order of the Carmelites lies between the grounds of St. Charles’s College and the imposing red-brick pile of the Marylebone Infirmary. Miss Vincent, matron of the Infirmary from 1881 to 1900, tells how the parents of one of the nuns on a certain day for three successive years begged permission to gaze from one of her upper windows into the convent garden.

Marylebone Infirmary was one of the earliest experiments both in taking the sick poor outside the boundaries of their parish and in arranging an Infirmary on purely hospital lines. Only a few wards were occupied when the hospital was opened by the Prince and Princess of Wales in I 8 8 . The excite-ment of this Royal visit is still remembered. In 1884 Marylebone Infirmary became also a Training School for Nightingale Nurses, financed from the Nightingale Fund. Part of the magnificent building which now covers several acres is on the site of an old pond, a pond shown on the Ordnance Survey Map for 1862-1869. Some years after construction the whole block sank and had to be underpinned.

Besides the large area of the Portobello Estate occupied by these extensive institutions, many builders in a small way of business bought land and put up houses for working-class tenants. One of the present dwellers in Rackham Street came there with her parents for the sake of their health about the year 1877. Building plots were then being taken up, but the north side of Rackham Street was open ground. The inhabitants were largely laundry-workers and casual labourers, an overflow from Kensal New Town. Edinburgh Road Board-school, now known as Barlby Road School, was placed in 1880 among the half-made streets near the Great Western Railway line ; and children from temporary schools in Kensal Town and at Rackham Street Hall were transferred to the new building.

When the school was first opened pigs were slaughtered in a shed close by, and for many years carpets were beaten on the adjoining open space. On a summer day the noise made by the beaters, and the dust from the dirty carpets, floated in at the open windows of the school. Carpet beating as a recognized industry has practically disappeared, though the cleaning of carpets by steam power is still carried on in Kensal Town. (Since those days factories of various kinds have been built, and the character of local occupations has considerably changed, but this corner has always remained rough and rowdy. Certain common lodging-house keepers, driven out by improvements in Notting Dale, have migrated to this district, and the Treverton Street area here and the Lockton Street area near Latimer Road Station, are reckoned among the black spots of the Borough of Kensington.)

Gradually during the eighteen-eighties the old track from Wormwood Scrubbs to Notting Barns was transformed into St. Quintin Avenue. At first there were heaps of refuse along the road, suggesting that it had served as a common dumping ground for rubbish. The earliest houses were built at the Triangle and in Highlever Road. It was by this road that troops on horseback would often make their way to their exercising ground on Wormwood Scrubbs. Sometimes these troops were accompanied by the Duke of Cambridge, and the loud voice in which he gave words of command is still remembered by one who lived as a child in Chesterton Road.

It was in 1881 that the parish of St. Clements was divided, and that the Rev. Dalgarno Robinson built the church of St. Helen’s on St. Quintin Avenue close to the site of Notting Barns Farm-house. This church, which resembles St. Clements in architectural features, now stands in a commanding position at the junction of several roads, and is a stately edifice, even though the tower is unbuilt. Mr. Robinson remained as vicar till his death in 1899. Until the beginning of the present century there was ” a great stretch of Common “ii between St. Helen’s Gardens and Latimer Road. Here cattle and horses grazed. This space had been curtailed in 1884 by the opening of Oxford Gardens School. This school originated in some of the leading tradesmen in the neighbourhood petitioning the School-board to provide State-aided education for their children, but at the highest possible fee. And Oxford Gardens was a 6d. school until fees were abolished in 1891.

North of St. Quintin Avenue was ” another great stretch of Common ” divided into three parts by Barlby Road and Dalgarno Gardens. (A little open ground still remains devoted to playing fields, but it is being encroached on from all sides.) By 1840 the eastern edge of Wormwood Scrubbs had been cut across by the Birmingham, Bristol and Thames Junction Railway, now the West London Junction Railway.

In 1852 it was proposed to use this detached piece of the Scrubbs, belonging to the parish of Hammersmith, as a Cemetery for Kensington people. The project was successfully petitioned against, and it has been made into a public Recreation Ground called Little Wormwood Scrubbs with an ornamental water-course along the upper reaches of the Rivulet. Strange tales are told of what has happened even within living memory in this distant portion of Kensington hemmed in by two railway lines. Here a man hanged himself. The question at once arose on which side of the ditch the man’s death had occurred, as that point determined which parochial authority should follow up the case.

An important tributary of the boundary stream rose near the Gas Works. This brook ran as a drain across the fields of St. Quintin’s Park, and was enclosed in ” a neatly bricked half-barrelled culvert with a perpetual flow of clean water with a curious acrid but not unpleasant smell. . . . At the elbow where the culvert turned, the brickwork rose to the height of six or seven feet.” This tower with two adjacent tunnels proved a tempting point for school-boy fights. The drain has disappeared, but the ground near by is still ” very mashy ” in wet weather. In this distant corner a gunmaker of Bond Street owned a shooting range provided with an iron stag which ran backwards and forwards on rails. Purchasers would test their guns on this stag, and at other times children rode on its back. By the eighteen-seventies it was derelict, ” a rusty fixed stag,” but ” being in a secluded spot, partly railed off by a high fence . . . it was used on Sunday mornings as a rendez-vous for prize-fights—prizes of from £10 to £15 being won by contest with the bare fists.” A hefty gipsy, who lived in the Potteries, unfortunately killed a man in an encounter behind the Stuck Stag. He was arrested, and got off with some difficulty. Drinking booths and roundabouts were erected on Little Wormwood Scrubbs when Bank Holiday Fairs were being held on the larger space beyond the railway embankment, and in summer-time the proceedings every Sunday evening were so disorderly that respectable people could not walk in that direction. It was only after the Wormwood Scrubbs Regulation Bill was passed, in 1879, that this corner settled down to an orderly existence.

North Kensington has now been traversed. Mere fragments of its story have been told, but these Chronicles will have fulfilled their purpose if they remind some readers of their own early days, or provide an explanation of certain characteristic features. Notting Hill, its former name, does not mean ” Nutting Hill ” in allusion to the rich woods which ” no longer cover it,” and assuredly is not ” a corruption of Nothing-ill.” But those who inhabit the neighbour-hood may well echo the brave words of Adam Wayne, in G. K. Chesterton’s inspiring story. When asked if he did not consider the Cause of Notting Hill somewhat absurd, ” Why should I? ” he said, ” Notting Hill is a rise or high ground of the common earth, on which men have built houses to live in, in which they are born, fall in love, pray, marry and die. . . . These little gardens where we told our loves. These streets where we brought out our dead. Why should they be commonplace? Why should they be absurd? There has never been anything in the world absolutely like Notting Hill. There will never be anything quite like it to the crack of doom. . . . And God loved it as He must surely love any-thing which is itself and unreplaceable.’