| The 1830s | Notting Hill in Bygone Days by Florence Gladstone |

Kensington Park |

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the village of Kensington Gravel Pits extended for three-eighths of a mile along the North Highway. The name seems to have been used for scattered buildings as far east as Craven Terrace or Westbourne Green Lane, now called Queen’s Road. When the pits disappeared the name was changed. No definite date can be given for this, but it is safe to say that, after 1840 the whole of the northern division of -“Kensington Parish was known as Notting Hill, and that the streets built near the turnpike both south and north of the main road were distinguished as Notting Hill Gate. They have continued so to the present day. The boundary line between Kensington and Paddington, now so complicated and devious, a hundred years ago followed a fairly direct course at the edge of fields, and was indicated by a ditch. The tiny Boundary House opposite Kensington Palace Gardens now covers the spot where the ditch emerged on the highway. (It has been a boot-shop since 1852.) See illustration on page 166. In 176o a malt-house occupied the Kensington side of the boundary. At Michaelmas 1786 the Gravel Pits Estate, on which the malt-house stood, was let for eighty-one years at £38 per annum to Mr. John Silvester Dawson, with the covenant that two houses and outbuildings should be placed on it. (A Mr. Dawson had a house on Bayswater Road in 1790.) The buildings erected were Stormont House, with a courtyard entered by an iron gate (this was on the site of No. t, Clanricarde Gardens). And an adjoining brewery called the ” Sun,” which apparently, from the Rate Books of 1812, was owned by Messrs. Trews & Co. Stormont House possessed a square staircase and good reception rooms. In the year 1808 it was a boarding school for young ladies kept by Miss Martha Tracey. She was there for nearly twenty years, but in 1827 Miss Elizabeth Tress seems to have taken over Miss Tracey’s school.’ By 1812 there was another school for young ladies nearby on the Uxbridge Road. This school, belonging to Miss Elizabeth Wilson, may have been at the ” Academy ” opposite Church Lane (see page 92), or it may have been at the Hermitage, Linden Grove, which a generation later was in use as a girls’ school.

Miss Wilson’s ” Semenary ” had a large garden, for the house and land were rated at £94. See illustration on the opposite page. The brewery built on the Gravel Pits Estate in 1800 had a short life. Before 1820) its grounds were covered with small ” tenements.” They formed a turning off the main road called Campden or Camden Place. To this double row of dwellings short side streets were added, named Anderson’s Cottages and Pitt’s Cottages. In 1838 Thomas Anderson was paying rates on nine houses. From early days these cottages seem to have been overcrowded, and by the middle of the century Camden Place was a notorious rookery, known as “Little Hell.” Two ladies living at Kensington Palace, Miss Desborough and Lady Gray, started a Ragged School in Camden Place. This probably was held in Stormont House, as about the year 1860, Mr. Gray of 4, Linden Grove, nick-named ” Gaffer Gray ” (father of the Rev. E. Ker Gray, see page 220), used to hold penny readings in a large room in that house ; really two rooms thrown into one. At the side of the house there was then the drying ground of a laundry. In the eighteen sixties nursemaid; on their way to Kensington Gardens, would hurry their charges past the end of this evil alley. (The writer well remembers the scene and the tiny shops and narrow pavement at this part of the high road.) It was only in 1867, when Mr. Dawson’s lease of the Charity Land fell in, that the whole place was cleared and Clanricarde Gardens was built on the site. Across the road was the red brick wall surrounding the kitchen gardens belonging to the Palace.

Somewhat further to the west the Mall ran at right angles from Uxbridge Road to Church Lane. It does so still. Here, besides one or two good houses, were some picturesque cottages known as Robinson’s Rents, and a row of three houses built in the time of Queen Anne by a Mr. Callcott. (These houses were pulled down to make room for Essex Church.) John Callcott, the musician, and Sir Augustus Wall Callcott, the painter, inhabited these houses early in the nineteenth century, and it was largely through the influence of the Callcotts that a group of artists settled in this suburb of London. Thomas Webster, R.A., afterwards Sir Thomas Webster, lived in the Mall, and the Horsleys, the musician father and the artist son, were at No. t, High Row, Church Lane. Delightful reminiscences of these artists with many details of local interest are given in the autobiographies of W. P. Frith, and J. C. Horsley.1 In the early years of the century a man named Mulready brought his family from Ireland and settled as a leather breeches maker in a shop between the Mall and Church Lane, close to the Gravel Pits Almshouses.

One of his sons was William Mulready, R.A. (1786— ‘863). On a moonlight night, about the year 1805, as young Mu!ready was returning home along the Bayswater Road from his art classes at Somerset House, and had reached the end of Westbourne Terrace, then a country lane, a man came out of the shadow of a tree and, presenting a pistol, demanded his watch and money. Mulready did not possess a watch but gave up the silver in his pockets. On reaching home he drew the man’s face from memory, and took the drawing to the police at Bow Street. A fortnight later he was called upon to identify the thief in a sailor who had been arrested for the murder of the toll-keeper at Southwark Bridge. At the age of seventeen Wm. Mulready married a sister of John Varley the artist. In 1809 the young pair were living in Robinson’s Rents, but in 1828, on the advice of Sir A. W. Callcott, Mulready moved to No. r, Linden Grove, a charming, low house with a good garden at the far end of a quiet lane. This house is now represented by No. 42, Linden Gardens. There were four sons, Paul, Michael, William (see page 62) and John, all of whom eventually gave drawing lessons. In Linden Grove, in 184.o, Mulready designed the penny postage envelope for Sir Rowland Hill, and he died there in 1863. (After his death the house was occupied by Alfred Wigan the actor, and it was used for the wedding reception of Sir Henry Irving.)

Two paintings of the Mall, Kensington Gravel Pits, by W. Mu!ready, dated 1812 and 1813, are at the Victoria and Albert Museum. The secluded and unlighted lane of Linden Grove also contained the Hermitage, already mentioned, and a few other two-storied houses, the largest of which was inhabited in 1827 by Thomas Allason, Esq. It is said that much house property between the Marble Arch and Notting Hill was built by this well-known architect. Linden Lodge or Linden Grove House was on the west side of the lane. At one time this was the home of one of the Drummonds, bankers. It was taken by Thomas Creswick, R.A., the land-scape artist, in 1836. There this kindhearted and jovial man and his sweet wife gave charming dances for the children of their artist friends. A small oil-painting of the house was made by Thomas Creswick for Mr. Thomas Allason. A copy by Mr. Herbert Jones hangs at the Public Library, Kensington. It is said that the Allasons lived there after Creswick’s death in 1869. Through the marriage of Miss Louisa Creswick Allason the property passed into the hands of Arthur Bull, architect, and his brother a surveyor. They pulled down ” the old house, filled up the lake, and built Linden Gardens and the shops in front on the site of the house, meadow and gardens. The Metropolitan Railway paid a considerable sum for permission to run under the estate.” George Grindle, Esq., was the last occupant, and the iron gates into Linden Gardens represent the gates into his drive.

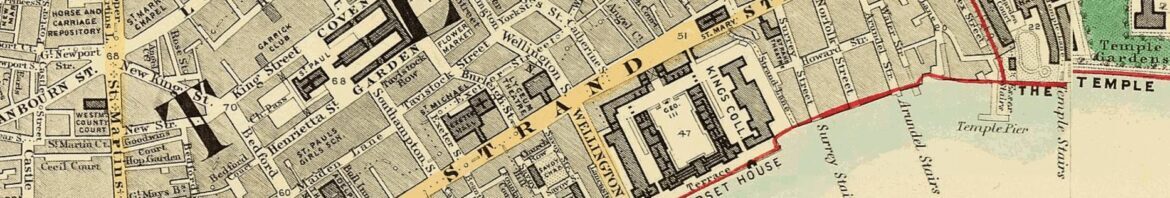

The regular village of Notting Hill seems to have begun west of the Mall and Linden Grove. In 184.0 it was still very countrified, with more cows than people, and with chickens scuttling across the road. There were few shops, and those were very small. Only two ” were above one story high ; ” one story over the shop. A graphic description of the place is given in a pamphlet by ” An Old Inhabitant ” who came into the neighbourhood in the year 1844, The following account is chiefly built up from his recollections, but valuable manuscript notes collected by Mr. T. Butler Cato have also been made use of, and other details are added from talks with local residents. The buildings mentioned can be fairly well traced on the maps in this book, but at the Public Library the actual number of houses and many other details may be discovered from the quaint plans in a book entitled Diagram of the Parish of St. Mary’s, Kemsington, for the rear 1846. The Happy Family who inhabited the village about 1844 included Mr. Fenn the tailor, who lived at the south-west corner of Linden Grove, and Mr. Brewer, who transacted the largest business of the village in the grocery, cheesemongery, and corn-dealing line. There was a candle-maker, who might be seen making candles in his cellar. His shop was reached up four stone steps. And there was a butcher’s shop, owned by a man named Price, which was entered by a gate at the top of three steps. When Mr. John Short came to see the place in 1858, with a view to taking it, he found Mr. Price seated on the steps fast asleep, with a pipe in his mouth. (That shop has developed into a very large business.) Another of the villagers in the forties was a Mr. Burden, rag and bottle merchant, who was an orator and a great man on the Kensington Vestry ; he was also a proprietor of Bayswater omnibuses. His wife kept a greengrocer’s shop. Poor woman, she was of such proportions that when she died the coffin had to be lowered by ropes from the bedroom window. Most of these shops were situated in what had been Greyhound Row between the Mall and Silver Street, the name then given to Church Lane. The Swan Inn, with its trough and signpost, standing back from the road at the corner of Silver Street, which is seen in the drawing of the second Notting Hill Toll Gate (see page 96), was faced at the opposite corner by a little butcher’s shop, and next to this was a brush shop, the proprietor of which, a most intelligent man, was a Chartist, and a great friend of Fergus O’Connor. Close to ” Brewer’s Cottages,” in what he loved to call ” Pittman’s Corner,” Mr. Matthew Pittman, stationer and newsagent was born, about the year 1842, and here he spent almost the whole of a fairly long life. Here too stood the Hoop Inn, projecting at an angle still occupied by licensed premises. Behind the houses on this south side of the road was a brickfield owned by a Mr. Clutterbuck, and it was here that Mr. Ernest Swain, the house agent, remembered bonfires being lighted and guys burnt in the early fifties. In 1844 shop windows were of common glass and the shops were lighted with oil lamps or candles. A crowd assembled night after night to see the illumina-tion when the first shop was lighted with gas. This was Mr. King’s Italian warehouse, one of the four shops built about 1844 over the front garden of ” Elm Grove,” a later name for the ” Academy.” The village pump stood on the site of the Metropolitan (District) Railway Station. When a proposal was made that it should be removed, public ” Indignation ” meetings were held and fierce threats were made of legal proceedings. Finally a tap supplying Water Company’s water was placed a few yards further to the west. For years this tap existed in front of No. 71 or 73, High Street. The ” Old Inhabitant ” suggests that an inscription might be placed on one or other of these houses with the words : ” Here stood the Village Pump.” He also suggests that a tablet might mark the position of the Village Pound, which harboured ” many a disconsolate donkey, horse or goat.” This Pound occupied the east corner of Johnson Street on Uxbridge Road. The house afterwards built on this spot was known as ” Pound House,” but the name is not to be seen on the shop opposite the Coronet Theatre. Adjoining the Pound was a blacksmith’s forge with a low gate, across which boys could watch the smiths at work and the fascinating sparks struck from the anvil. Uxbridge Street lay behind the houses on this side of the way, and was connected with the high road by Turnpike Farm Street, now Farmer Street, and Johnson Street which crossed what had been Johnson’s Brick Fields. Semi-rural dwellings may still be traced in this quarter, but relics of the past are fast disappearing. The Notting Hill Toll Gate crossed the high-road close to the village pump. The picture of the gate as it appeared between about 1835 and 1856, on page 96, is adapted from a well-known drawing which hangs in Kensington Public Library. This gate was replaced ” in the fifties ” by a toll-house in the middle of the road at the end of Portobello Lane, and gates crossed the road diagonally from No. 79, High Street, as shown on page r.z4. Bars or subsidiary gates were placed across turnings off the high-road in order that the payment of tolls should not be avoided. One bar was in Silver Street, opposite Campden Street, and others at Portobello Lane, now Pembridge Road, at Addison Road and at Norland Road. Some of these bars were removed earlier than others, but all the remaining gates and bars were done away with by Act of Parliament on July 1, 1864.

Old inhabitants of Notting Hill can remember the public rejoicings and the procession of vehicles which passed through the gates when they were opened at midnight on that day. The last people to drive through Notting Hill Gate were Mr. and Mrs. Randall of 4, Lansdowne Crescent. But to return to the north side of the road. The shops west of Linden Grove were in Kensington Terrace and Elm Place. The numbering of the houses in these short terraces was most erratic and far from consecutive. The late eighteenth century house with two bays (see page 58), was reckoned as part of Elm Place. It has a quaint circular staircase and the doors are curved. In one room is a fireplace with a coat of arms belonging to the Pilkington family. Part of it is now used as the West London Branch of the Society for Teaching the Blind. It is known as Vestris House because Lucia Elizabetta Bartolozzi, Madam Vestris (a granddaughter of the famous engraver), ” that most incomparable of singing actresses,” at one time lived here. Madam Vestris, the first woman to become the lessee and manager of a theatre, was born in 1797. In 1838 she was married at Kensington Church to the actor, Charles James Matthews, and in 1856 she died. Her portrait appears on page 58. Another house, which was demolished when the Metropolitan Railway was made, was known as the Vicarage. It was well-built and had a fine staircase, but was inhabited in the eighteen-sixties by the family of a postman named Brownridge. Beyond Elm Cottages, now represented by Pembridge Gardens, a farm occupied the site of the station of the ” Tube ” or Central London Railway. (Was it Turnpike Farm ?) In 1840 this property was owned by John Hall, Esq., probably a son of Christopher Hall (see page 62), but before 1840 the farm had been replaced by a house known as Elm Lodge. The charming garden and orchard of this house were bounded on the west by the hedgerows of Portobello Lane, and the fruit was often stolen. Elm Lodge was inhabited by the Rev. J. W. Buckley and his family. Mr. Horsley, in his Recollections, tells how ” Willy Buckley ” watched all night in the garden, and caught a man with a sack stealing apples ; how he pushed the man before him through the house, the paved yard and entrance gate, without waking the family, and finally handed him over to one of the ” newly-invented constables ” whom he found asleep ” leaning against one of the newly-invented lamp-posts,” In 1844 Elm Lodge was the residence of the Rev. Mr. Holloway, minister of Percy Chapel, Fitzroy Square. After his death it was occupied by the Rev. Mr. Gordon, a Presbyterian minister who for some years held services in a building attached to his house. The ” Devonshire Arms ” was afterwards built on part of the Elm Lodge grounds. The group of ” Elms ” : Elm Place, Elm Grove, Elm Cottages and Elm Lodge, have disappeared with the elm trees. Mulberry Walk is Palace Gardens Mews, and the limes of Linden Place on the south side of the main road, and Linden Grove on the north side, are now only recalled by the collection of houses comprised in Linden Gardens. The junction of Weller Street, now Ladbroke Road, and Portobello Lane, now Pembridge Road, was widened to accommodate the entrance to the Hippodrome. The ” Prince Albert Arms ” and the ” Hope Brewery ” were placed just outside the gates. It is at this corner that a portion of the old-world village can be seen practically in its original state. Probably few residents in the neighbourhood know of the existence of the quaint lane called Bulmer Place, with its tiny cottages and gay front gardens. It is reached by a covered passage at each end. The local fire-engine was kept in ” Tucker’s Shed ” at the upper end of Ladbroke Road.? Later on, when firemen ceased to be a voluntary body, a fire station was built further down the road next door to the police station, which was just above the present palatial erection. The ” Coach and Horses,” No. 108, High Street, was still a small and primitive tavern. The proprietor, Mr. Drinkwater, got into trouble for selling spirits on the Hippodrome grounds without a sufficient license, but the tavern itself was reputed to be quiet and respectable, instead of being a refuge for highway-men as of old. It was rebuilt in 1863. In 1870 Mrs. Drinkwater was in possession, and this was the office for coaches to Hillingdon and Hayes, and for omnibuses to Hanwell. Somewhere between the years 1810 and 1825 Montpelier House, Nos. 128 to 130, High Street (see illustration on page 58), became the residence of Joseph Hume, F.R.S., some-time surgeon in the East India Company, one of the leaders of the Radical Party in Parliament. Philosophic and literary discussions must also have taken place here, for, before 1830, Charles Lamb and his friends Hazlitt, the essayist, and Godwin, the philosopher, are said to have been constant guests at this house. Joseph Hume married the daughter of a wealthy East India proprietor, and had six children. (Mrs. Augusta ‘Webster, poetess and social worker in Kensington, was a granddaughter.) He died in 1855 four years before Peter Alfred Taylor, M.P., came to live at Aubrey House ; but Joseph Hume had been closely connected with P. A. Taylor the elder, in the Corn Law agitation of the eighteen-forties.

Almost next door was the “Plough,” equally removed in character both from the original inn on the North Highway, and the large modern building at 144, High Street. The map of 1831, on page too, shows that the ground at the back of the ” Plough ” was arranged as a tea garden. Bayswater abounded in public open-air resorts, but this seems to have been the only place of the kind in Notting Hill. These pleasure grounds had none of ” the romantic associations and historic dignity ” of such eighteenth century gardens as Vauxhall or Ranelagh. They were used by ” the lower orders.” In the tavern garden a man might sit with a friend, or whole families might assemble to take a modest repast. According to a London Guide of 1846, in such places the amusements were innocent, the indulgence temperate, and a suitable mixture of female society rendered them both gay and pleasant.

Between the “Plough” and Ladbroke Terrace stood a large white house in a garden surrounded by a high wall overhung with ivy, against which, about the year 1850, an old woman used to sit selling apples, Bellvue House was inhabited by a Dr. Barnes, but by 1870 it had disappeared.

Across the main road the winding pathway of Plough Lane climbed the hill. Plough Lane ended in Campden Passage, a footpath between the premises of the two water companies. At the corner (now occupied by Messrs. Pearson’s ironmongery stores), was a dairy farm called Notting Hill Dairy, locally known as ” Shoesmith’s ” ; and a little way up the hill was a good old house which seems to have ended its career as a laundry. Below this house, at the north-west corner of Plough Lane, Mr. R. T. Swain, in 1848, built a cottage to which he brought his young family from a house in Shepherd’s Bush. Here, in 1849, he established the business of auctioneer and house agent, a business which is still carried on in Notting Hill Gate. The Lodge, as it was called, had a large garden full of fruit trees and roses, but, although it was so near to the waterworks, and built for his own use by a house agent, all water needed for domestic or garden purposes had to be fetched from a pump in the main road. The Lodge was demolished in 1870 to make way for the much-needed thoroughfare of Campden Hill Road. The village of Notting Hill ended at Ladbroke Terrace, as High Street, Notting Hill Gate, ends there still.

But building was being carried further west. By 1824 Mr, Christopher Hall had given up Notting Hill Farm, rated at £520, though probably property at Notting Hill Gate was held by the family. A man named Paul Turley purchased Mr. Hall’s farm-and for building purposes. The farm-house was pulled down and a terrace of little houses facing east, Nos.. 11 to 19, Ladbroke Grove, was built. According to one of the leases these houses appear to have been inhabited by the year 1825. Before 1827 a most charming row of houses on the main road, known as Notting Hill Terrace, now forming part of Holland Park Avenue, extended almost as far as Ladbroke Place, now Ladbroke Grove. In 1827 Mr. Turley’s name disappears, and it is the ground landlord, Mr. James Weller Ladbroke, who pays the rates on the Notting Hill Farm property. Notting Hill Terrace was faced on the south side of the road by Notting Hill Square and certain villa residences. Hanson’s or Notting Hill Square, now Campden Hill Square, was commenced between 1823 and 1825 on part of the Notting Hill House estate. It was built by Mr. Joshua Flesher Hanson, the purchaser of Notting Hill House ; first the houses on the east then those on the north, and lastly those on the west side.

A delightful picture of the scene, as it appeared in 1834, three years before the making of the race-course, is provided in the comic drawing, ” The Flight of the Hunted Tailor of Notting Hill,” by Henry Aiken, Junior, shown opposite. (Mr. Aiken’s pictures of the steeplechase, in 1841, have already been mentioned.)

The legend runs that one Sunday morning a tailor went out to shoot birds. In doing this he unfortunately broke a window, besides breaking the Sabbath. For these mis-demeanours he is shown in the picture being chased by the populace past the houses of Notting Hill Terrace. A country road, evidently Ladbroke Grove, joins the thoroughfare, St. John’s Hill appears in the distance, and a man in the foreground is seen climbing over the palings of the square garden. Each map or plan of the forties and fifties gives variations in the naming of the new streets, and the complication of small ” terraces ” and ” places ” is most confusing. It is a matter for thankfulness that they are all now included in Holland Park Avenue. A series of mews runs behind all the terraces on the north side of the road, showing how necessary it was at this period to own a private vehicle. Boyne Terrace and Grove Terrace lay west of Ladbroke Grove.

For a while the south end of Lansdowne Road was called Great Circus Street or Liddiard’s Road, and Clarendon Road was Park Street. Portland Road, the road to the Hippodrome stables, was chiefly known as Norland or Hippodrome Lane. Beyond Pottery Lane was the Norland Nursery, covering what had formerly been a large pond. On this nursery ground the three houses of Castle Terrace were placed in 1861. Views of this part of the road are shown, page 116, but before 1857, the date of these quaint engravings, shops had been added over the front gardens of many of these houses. The grounds of Holland House then reached down to Uxbridge Road, and were enclosed by a rustic paling, but a year or two later thirty-seven acres of the estate were bought by the Messrs. Radford Brothers, and the twin rows of large houses known as Holland Park were commenced on land formerly occupied by oaks and may-trees.i The map on page 120, shows the position of Norland Terrace and Norland Place, rows of houses facing the high road, separated by Norland Square. This square was built between 1837 and 1846 on part of the site of Norland House and its walled-in grounds. Norland Place was divided by Addison Road North (since 1915 called Addison Avenue). At the north end of this attractive road the church of St. James’s, Norland, was placed in 1845, the architect being Mr. Lewis Vulliamy, a son of the Benjamin Vulliamy who had sunk the famous overflowing well nearly fifty years earlier. See illustration on page 11c). Lewis Vulliamy had also been the architect of St. Barnabas, Addison Road, a church known as Kensington Chapel when built in 1827. The name of Addison is, of course, derived from Joseph Addison, the writer, who married the widow of the sixth Lord Holland. He died in 1719.

Two small terraces, some cottages and stables and the coaching inn, the Duke of Clarence, stood beyond Addison Road on the south side of the way, faced by Norland or Royal Crescent. Both names were used when the crescent was being built in 1846. See illustration on page I to. Between Royal Crescent and Norland Road the main road turns slightly to the north, and here were placed the twelve little houses of Union Terrace. The boundary ” rivulet ” already ran in a sewer under Royal Crescent Garden, and Norland Road had become the western boundary of the parish. Norland Market, the outstanding feature of Norland Road, dates from the time when there were few local shops, for it must be remembered that the buildings along Uxbridge Road were all private residences. A row of small houses on the east side of Norland Road bears on its central pediment ” Shepherd’s Bush and Norland Market.” It is said that ” The Market ” differs from other street markets in that the stall-holders have no stands elsewhere. With the passage of years, and the development immediately to the north of a ” deplorable quarter,” this market has changed greatly, but, to those who are familiar with the scene, Mr. Harold Begbie’s description in Broker: Earthenware, Chapter I, appears unnecessarily lurid. By 1844, the southern part of ” Norlands ” or Norland Town had been laid out practically in its present shape, although only a few houses were built along the various roads. Compare the difference in this part between the map of 1841 (page 76), and the map of 1850 (page 120). Almost every house stood in its own garden. Princes Place and the other small turnings off Queen’s Road, now Queensctale Road, St. Ann’s Villas and Darnley Street belong to this period. The brick houses with charming diagonal work and stone facings in St. Ann’s Villas were long known as the Red Villas. A tablet let into the front wall of Nos. 1 and 2, St. James’s Square, announces that the first stone of this square was laid on November 1, 1847, therefore more than two years after the church was completed. For some years after 1847 there were no houses on the north side of the square : the garden abutted on open ground.

St. Catherine’s Road, now Wilsham Street, as late as 1850 was nothing but a footpath leading from the south end of Latymer Road to Pottery Lane ; one small terrace of houses, Cobden Terrace, stood at its western end. William Street, now Kenley Street, then a row of small semi-rural houses with long front gardens, was the only road north of St. James’s Square. Well on into the sixties it was inhabited by the families of City clerks. A narrow footbridge across a small stream, which seems to have been connected with the open sewer in Norland Lane, gave access to the allotment gardens and marshy land which separated William Street from the Norland Pottery Works and the notorious colony of pig-keepers already described.