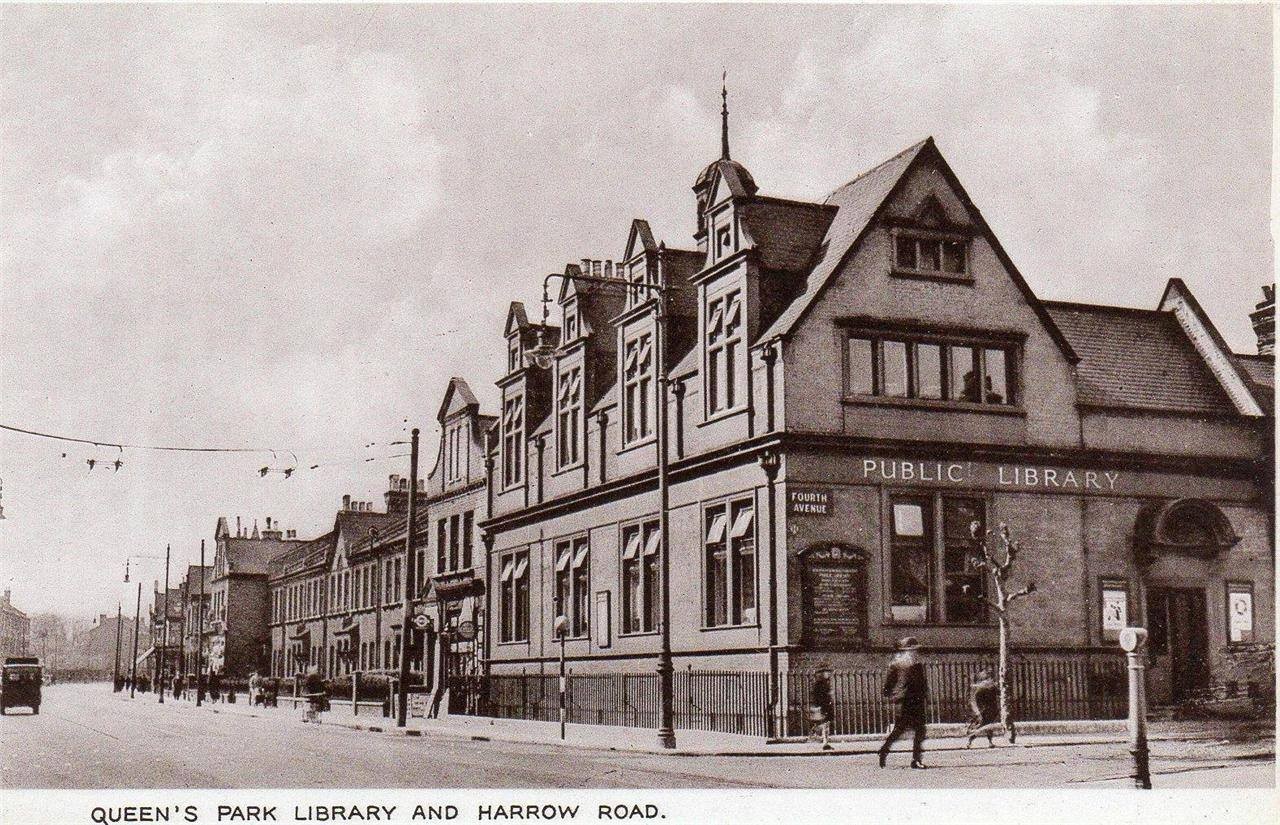

Once, Fourth Avenue run all the way south to the Harrow Road but post-Second World War redevelopment changed the road layout at the southern end.

The Queen’s Park Estate, like Kensal New Town on the opposite side of the Grand Union Canal, began in a geographical curiosity known as ’Chelsea Detached’ – a part of the parish of Chelsea situated miles away from the remainder of Chelsea.

In the 1740s, the local fields were pasture. There was a wooded area beside Kilburn Lane and some farm buildings on the Willesden side of the lane. The Grand Junction Canal was later cut just south of Harrow Road, leaving much less than half of Chelsea Detached to the south.

In the 1830s and 1840s, the original part of Kensal Town was laid out stretching up to the Chelsea parish boundary but no further. The northern part of Chelsea Detached belonged to All Souls’ College, Oxford.

Confined by the canal to its north, Kensal Town did not urbanise across the Grand Junction (later the Grand Union) and the remainder of Chelsea Detached – now Queen’s Park – stayed mostly as fields until the 1870s. A few houses were built along Kilburn Lane – effectively an extension of Kensal New Town. The new town was served from 1843-4 by St John’s church, which in 1865 stood with only two nearby houses and the National school on the east side of Kilburn Lane north of Harrow Road.

The first part of the Queen’s Park Estate similarly, when laid out, only stretched to the Chelsea Detached boundary so that by later in the 1870s, the whole of the strange bit of Chelsea was built up and both Kensal Town (after the 1850s) and Queen’s Park (1880s) only later leapt the parish border.

In 1900 the northern part Chelsea Detached was politically absorbed into the then-new Metropolitan Borough of Paddington. Kensal New Town was transferred to Kensington Metropolitan Borough.

Queen’s Park was built up comparatively quickly, by the Artizans’, Labourers’ and General Dwellings Company. Two adjoining blocks of land of 49½ acres and 24 acres were bought in 1874-5 from All Souls’ College. The purchase was announced, together with the new name of the estate and plans to accommodate 16 000 people, in 1874.

The site was to have treelined roads, with four acres in the centre reserved for recreation. Gardening was to be encouraged and there was to be provision for an institute, cooperative stores, coal depot, dairy farm, baths, and reading rooms (but no public house).

Avenues numbered from one to six were laid out leading north from Harrow Road and were joined by long crossstreets, at first called merely by the letters A to P but soon given names in alphabetical order.

Building took place in several roads at the same time. Houses were dated 1873 and 1874 on the east side and 1876 on the west side of Sixth Avenue, 1880 in Fifth Avenue, 1875 in Caird Street at the east end of the estate, and 1876 in Oliphant Street at the far end and in a nearby shopping parade in Kilburn Lane.

Financial difficulties in 1877 brought delays, rent increases, and building on the intended open space, but renewed progress had led to the completion of 1571 houses by 1882, when a further 449 were under construction. The whole area west of First Avenue had been built up by 1886.

Queen’s Park, like the company’s other four residential parks in London, was the result of a well supported effort to improve working-class conditions. It came to be seen as a success in comparison with Kensal New Town.

All 2200 houses at Queen’s Park were occupied in 1887, when the rents were much lower than those nearby. By 1899 the estate was ’carefully sustained in respectability’, there was a waiting list for tenancies, and rents were never in arrears. Only a fifth of the inabitants lived in poverty, compared with more than 55 per cent in Kensal New Town, and those that did so may have lived outside the company’s estate, around Herries Street.

The north-east corner of Chelsea Detached was acquired by 1874 by the United Land Co. which eventually laid out Beethoven Street, Mozart Street, Herries Street, and Lancefield Street. These terraced houses were tightly packed – Beethoven and Mozart streets had been built up by 1886.

In the period between the World Wars Queen’s Park changed very little, its rented houses continuing to be in demand.

Damage to Queen’s Park during the Second World War included destruction by a land mine at the corner of Ilbert Street and Peach Street, where Paddington council was building Queen’s Park Court in 1951. The Artizans’ company disposed of its remaining Queen’s Park properties in 1964. In 1978 the houses along most of the southern edge of the estate, between Droop Street and Harrow Road from Sixth Avenue almost to Third Avenue, made way for Westminster’s Avenue Gardens consisting of 11 blocks named after trees.

On the border of Queen’s Park, between Lancefield Street and Third Avenue, in 1970 Westminster Council began work on the Mozart Estate which was intended for 3450 residents and was later extended northward as far as Kilburn Lane. The completed estate in 1972 formed a rectangle bisected by Dart Street. St Jude’s church was demolished and the north-south Lancefield Street and Herries Street were reduced to short cul-de-sacs.

Most of Queen’s Park was declared a conservation area in 1978.

Rebuilding in Queen’s Park has consisted chiefly of Queen’s Park Court and Avenue Gardens surrounding the Victorian-era Queens Park Public Library on Fourth Avenue.