| Table of contents | Notting Hill in Bygone Days by Florence Gladstone |

Gravel Pits |

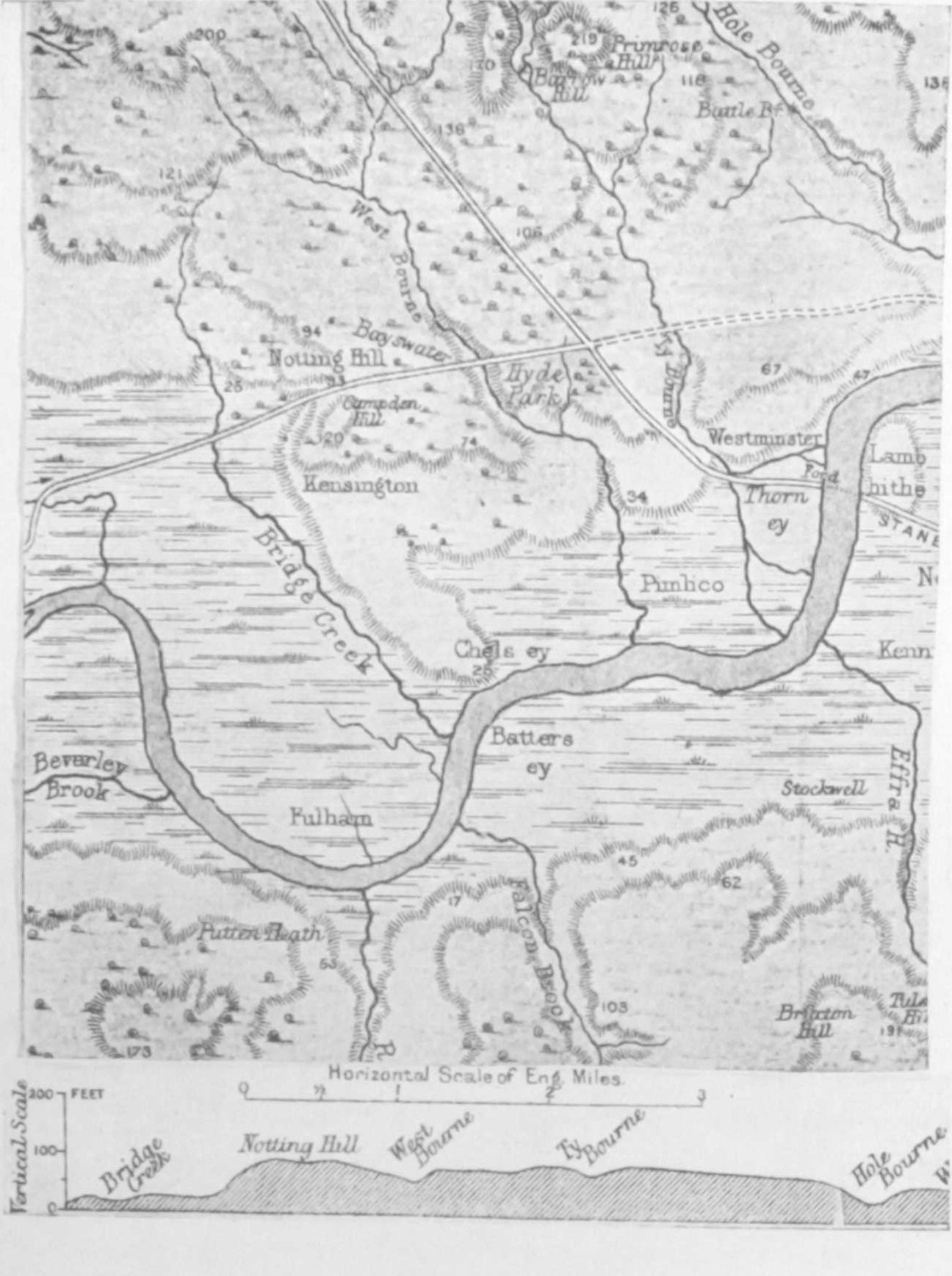

On the north side of the Thames as it crosses London there is a range of low hills. Beginning with Tower Hill close to the river, the range ends with Campden Hill, three-quarters of a mile from its bank. Each hill is divided from the next by a stream. These streams rise on the northern edge of the Thames Valley and fall into the left bank of the winding river. Campden Hill, Bayswater Hill and the ” Knoll ” surmounted by St. John’s Church form one group which practically constitutes Notting Hill. This high land is bounded on the east by the Westbourne or Bays ‘Water, and on the west by a “rivulet” known as Bridge Creek or Counter’s Creek. Both the Westbourne and Counter’s Creek are now carried underground.

The map above shows this formation of hill and stream. It also shows two important Roman roads which approached the town of Londinium from the north and west : Watling Street, now Edgware Road, and that portion of the Great West Road at present represented by High Street, Notting Hill, Bayswater Road and Oxford Street. These roads were cut through densely wooded country, known at a later date as the Forest of Middlesex, and there seems to be little doubt that, before the time of the Romans, both Edgware Road and Bayswater Road had been British trackways.

(Note: In 1916 placards posted in the stations of the Central London Railway stated that Holland Park Avenue was the Via Trinobantia of the Romans, the chief road of the late Celtic Kingdom of the Trinobantes whose capital was Colchester)

Mr. Reginald Smith, F.S.A., of the British Museum, considers that another trackway, not marked on this map, followed the high ground nearer to the river. This also probably was developed by the Romans, and subsequently became the road through Knightsbridge, Kensington and Hammersmith. These two roads joined at Brentford. At Notting Hill Gate the Great West Road ran on the edge of a terrace ninety-five feet above the sea. The forest was not so dense here as it was further to the north, and the high land across the Thames would be visible. It has been suggested that a beacon may have been placed at Notting Hill Gate to correspond with another on the hill-top south-west of Egham.

Except for the name of High Street (Street being derived from Via Strata, the paved way), there seem to be no actual relics of the Roman period within the boundaries of Kensington parish. It has, however, been claimed that a trough of broken masonry, now preserved in the garden of St. John’s Vicarage, Ladbroke Grove, may have been part of a Roman sarcophagus. This stone trough was discovered about 1850 when the foundations of No. 1, Ladbroke Square were being prepared : a likely position for a Roman grave close to a main road. Being a coffin burial the date would be after A.D. 250. The final departure of the Romans early in the fifth century was followed by a period of disorder. Middlesex lay between the quarrelsome kingdoms of Mercia and Wessex and was in a disturbed condition for many years. But, probably, somewhere about A.D. 700, a party of Saxon immigrants, ” sons of Cynesige,” discovered a favourable spot above the marsh lands of Chelsea and Fulham. And here, on the hill-top between the old roads, they founded their little ” tun ” or village. For Chenesitun, the Kensington of those days, only consisted of a few wooden homesteads with barns and cattle sheds, surrounded by a rough stockade : an island of cultivation in the midst of woodland and common. About the same time Poedings, or ” sons of Padda,” settled dose to Watling Street, and another Saxon family, the Cnot-tingas, or ” sons of Cnotta,” may have made a clearing for themselves in the denser wood to the north.

No less an authority than Dr. Walter W. Skeat suggests this Saxon solution for the name of Notting Hill. Other writers have thought that the encamp-ment was founded by followers of King Knut. Whether Saxon or Danish in its origin the little colony seems to have been entirely wiped out before the Norman Conquest ; nothing but the name remaining to testify to its former existence.4&5 The popular belief that Notting Hill owes its name to the nut bushes which grew upon its slopes is a pleasant, but untenable, tradition. The name occurs in the Patent Rolls for A.D. 1361. There it is ” Knottynghull,” proving that the ” k ” is original as is also the double ” t.”

The old village of Knotting in Bedfordshire is thought by some antiquaries to derive its name from ” Noding,” a Danish term for a cattle pasture. In the Cotswolds there is an entrenched camp known as Notting Hill.

The Forest of Middlesex has already been mentioned. William Fitz-stephen’s well-known description, written about 1170, tells of ” densely wooded thickets, the coverts of game, red and fallow deer, boars and wild bulls.” There are no records of such game in this district, but remains of a wood can be traced on St. John’s Hill, and there is other proof of forest land within the present area of North Kensington. At the British Museum is a Deed of the time of Edward the Confessor, which states that Thurstan, Chamberlain or Master of the King’s Household, bequeathed his share of the Manor of Chelsea for the benefit of King Edward’s new religious foundation at Westminster.

Among lands belonging to Chelsea was a detached piece of woodland, given specially to supply faggots for the Abbey fires, and acorns for the Abbot’s pigs. This portion of woodland, 137¾ acres in extent, is now covered by the houses of Queen’s Park Estate and Kensal Town. Chelsea Outland is shown on the map of 1833 on page 40, where also are seen many local names recalling the trees : Acton, or ” place of oaks,” Old Oak Common and Six Elms, Wormholt or Wormwood Scrubbs and the names ending in ” den,” like Neasden and Harlesden, which were valleys where swine might be fed.

At the date of the Deed mentioned above, the Manor of Chenesitun was held by Edwin, one of Edward the Confessor’s ” thegns.” ” Edwin the Thegn suffered the fate of most Saxon noblemen,” for, before the Domesday Book was drawn up in 1086, the Manor of Chensitun had been granted by William the Conqueror to Geoffrey, Bishop of Coutances, under whom it was held by Aubrey de Vere. It became Aubrey de Vere’s freehold property during the reign of William Rufus. The Survey of the Manor in 1086 may be read both in Latin and English in Mr. Loftie’s book. A picture is there drawn of the priest or rector, the eighteen farmers and seven slaves with their families, 200 to 240 persons in all, cultivating some 1,400 acres, and living near the church, which was practically if not actually on the site of St. Mary Abbots.

For the pasturage of their cattle there were about 500 acres of common land, making 1,900 acres as against the 2,290 acres of to-day. ” But while the men went forth to follow the plough, to sow their seed or garner their corn, the women and children drove ‘ the cattle of the town ‘ to the pasture, and their herd of 200 pigs to pick up beech mast and acorns in the woods to the northward.” Aubrey de Vere and his successors owned the Manor of Kensington from the reign of William I to that of James I, a period of over five hundred years. ” De Vers ” had been amongst the noblest of the old Norman aristocracy. Later on they were created Earls of Oxford, and held many important State Offices. They took part in the Crusades, they fought at Crecy, Poictiers and Agincourt. Twice at least their lands were forfeited to the Crown, but were restored to subsequent holders of the title, and the twelfth Earl of Oxford and his son were beheaded. But, as they were always absentee landlords, it is probable that everyday life in Kensington was not deeply affected by the fate of the heads of the house.

During the lifetime of the first Aubrey 270 acres of land, extending from Church Street to Addison Road, was granted to the monastery of Abingdon, and became the independent Manor of Abbot’s Kensington. Gradually the remaining portion of the parish was divided into three parts : the separate manors of Earls Court, covering what is now known as South Kensington, the Manor of West Town, originally called ” the Groves ” and consisting of fields west of Addison Road, and the Manor of Notting Barns with which these Chronicles are chiefly concerned. The story of how the De Veres parted with this northern division of Kensington is so characteristic of the times that it must be given in some detail.

When John the twelfth Earl of Oxford and Aubrey his eldest son were beheaded in February 1462, by order of Edward IV, on account of their allegiance to the House of Lancaster, their lands, including the Manor of Abbot’s Kensington and Notting Barnes, valued together at twentv-five marks, were forfeited to ” the Lord the King.” Shortly after this for-feiture the King’s brother, afterwards Richard III, was receiving ” the issues and profits ” from these lands, as if they had been granted to him ; whereas, evidence given in 1484 and in 1496 proves that ” Richard, Duke of Gloucetir ” only enjoyed and retained them ” of his inordinate covetyse and ungodly dispocion.” Added to this ” by compulsion, cohercion and emprisonment ” he had forced the widow of the beheaded Earl to release to him divers other lands, thus reducing her and her daughter-in-law to a state of absolute want.

Meanwhile ” John Veer,” the thirteenth Earl, was in exile and was suffering many hardships. When, however, Henry Tudor, Duke of Richmond, felt himself strong enough to make a bid for the throne of England, the Earl of Oxford joined his company. In 1485 they fought side by side on the fateful Field of Bosworth, and shortly after Henry VII had become King, the whole of the Vere family were reinstated in their lands, honours and dignities. But, although he had been made Constable of the Tower, the Earl was so impoverished that he found it necessary to realize money on his estate, and in 1488 ” the Manor of Notingbarons ” passed into the hands of William, Marquis of Berkeley, Great Marshall of England. By means of a somewhat secret transaction with Sir Reginald Bray, the Manor was then sold for four hundred marks to Margaret, Countess of Richmond and Derby, mother of the King. Probably ” Lady Margaret ” hoped in this way to ease the burdens of a staunch supporter of her son’s cause. Shortly after the purchase was completed this Manor, valued at £10 per annum, was joined with other properties in the county of Middlesex, making in all the ” yerely valow ” of £90.

These properties were conveyed by the Countess to the Abbot, Prior and Convent of Westminster, with the specification that after her death the income should be spent on masses for her soul in the Abbey Church of Westminster, and for the upkeep of the professor-ships which she had founded at Oxford, and in St. John’s and Christ’s Colleges, Cambridge. At the death of Lady Margaret in June 1509, in the midst of the Coronation festivities of her grandson, Henry VIII, these lands became the property of the Abbey, and were held by the Abbot ” as of his Manor of Paddington by fealty and twenty-two shillings rent.” When the Earl of Oxford had parted with the Manor of Knotting Barns in 1488 it comprised ” a messuage, 400 acres of land fit for cultivation, 5 acres of meadow, and 140 acres of wood in Kensington : 545 acres in all.”

Another 140 acres, forming the Norland Estate, and certain fields called North Crofts lying along the old Roman road, belonged to the Manor of Abbot’s Kensington. These lands with the Manor of Knotting Barns seem, practically, to have covered the irregular triangle of North Kensington. In a Deed of 1526, ” The Manor called Notingbarons, alias Kensington, in the Parish of Paddington ” is described as including ” dyvers lands and tenements in Willesden, Padyngton, Westburn and Kensington in the countie of Midd ; which maners, landes and tenements the said Princes late purchased of Sir Reynolde Bray, Knight.” Mr. Robins, see note 8, believed that all this land and more was included in the parish of Paddington. A simpler explanation seems to meet the case.

By the middle of the fifteenth century the forest in this part of Middlesex had almost disappeared, and was being replaced by pasture land, used either for grazing purposes or for hay. The scattered meadows, purchased to increase the property which Lady Margaret was about to place in the hands of the Abbot of Westminster, may well have been grouped together under the name of the principal farm, which was in Kensington, while the holder of the property lived in Paddington. This at least was the condition of affairs some thirty years later. All this is distinctly puzzling. Naturally there is also much variety in the forms of the name. Knottyng-hull, the steep hill on the high road, is mentioned a century earlier than the Manor House with its spacious barns which stood amidst the pastures to the north.

But in 1462 Knottyngesbernes is met with, and Knottinge Bernes in 1476, whilst the Manor appears as Notingbarons 1488, Notingbarns 1519, and Nuttingbars 1544. Other varieties occur later on.

After the death of Lady Margaret the Abbot promptly leased the Manor to a wealthy citizen of London described variously as Roper, Fenroper, Fenrother, etc. Alderman Robert Fenrother held the post of Sheriff in 1512 and again in 1516. A member of the Goldsmiths’ Company and a Yorkshireman, he owned estates in various parts of England, but lived in the heart of the City, and when he died in 1526 he was buried in the Church of St. John Zachary at the corner of Mayden Lane. The Wills of Robert and Juliana, his wife, afford much information on the life and surroundings of a rich and worthy merchant family in the early sixteenth century. The Fenrothers had three daughters, Audrey, otherwise Etheldreda, Julian and Margaret, the eldest of whom married Henry White, gent., who was a sheep farmer.

Notes from the Parish Church Registers, in Kensington Parish Magazine for 1884 and subsequent years, Mrs. Henley Jervis, who was an indefatigable investigator, came to the conclusion that in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries Kensington South as well as North was a wool-producing district.

At the time of their marriage, about 1518, Nottyng Barnes was given over to the young couple for their use, and was to become their property after the death of Mistress Fenrother. But, whereas in 1488 the Manor had covered 545 acres, in 1526 it was reckoned at 420 acres, though the value was still £10 per annum. It now consisted of 40 acres of arable land, 140 acres of meadow, 200 acres of wood, 20 acres of moor, 20 acres of furze and heath and 40 shillings rent. A farm-bailiff may have been put in charge of the Manor farm, for the Whites made their home at Westbourne or Westbourne Place – a house which stood on ground now covered by the Lock Hospital. This house was superseded by the handsome mansion of the same name built for himself by Isaac Ware in 1794.

In 1527, a year after his father-in-law’s death, ” Henrico White, pastur in padington ” in conjunction with William Person, obtained from Lord Sands, owner of Chelsea Manor, a lease for twenty-one years of the four pasture closes, or fields, adjoining Notting Barns, and covering the whole area of the detached portion of Chelsea. Up to the fourteenth century this had been forest land, known as Kingsholt in 1365. Before 1535 both Henry White, Esq., and his wife Etheldreda had died, probably from some infectious disease, and when Mistress Fenrother passed away at her house in Mincing Lane, early in the year 1536, Notting Barns with other estates was placed in trust for the orphan grandchildren, Robert, Frances, Albone, or Alban, and Elizabeth White, until they should marry or become of age. The young Whites lived on at Westbourne for another seven years.

An Ecclesiastical Valuation, carried out at the King’s command in 1535, had opened the eyes of Henry VIII to the extent and character of lands belonging to the Church, and he determined to seize this rich booty. First the smaller religious houses and then the larger monasteries were despoiled. By the year 1540, the Lady Margaret’s munificent gift to the Abbot and Convent of Westminster had become vested in the Crown, and the King, as owner of these lands, confirmed Robert Whyte, the eldest son of Henry White, in the ” messuage called Westbourne-place with certain lands therto belonging.” In 1541 Master Whyte attained his majority, and paid a tax of 15s. on his lands in Kensington.

Five years before this date the King had ousted Baron Sands from the Manor of Chelsea, and had granted him in exchange a Priory in Hamptonshire. In 1543 the Manor of Chelsea was assigned as a marriage portion to Catherine Parr. Robert White owned some house property in Chelsea, and the lease of the four fields granted to his father in 1527 had not yet expired. It may be that King Henry became aware of the attractions of Knotting Barns when examining into the titles of the proposed gift to his sixth bride, for, in that same year of 1543, Robert White was forced to surrender his lands and the home where he and his brother and sisters lived, and to accept instead the Manor of Overburgate. In the Deed of Exchange the transaction is thus described : ” Robert White, esquire, bargained and sold to the King his manor of Knotting Barns, in Kensington, with all messuages, cottages, mills, etc., to hold to the King, his heirs and successors, in exchange for the Manor of Over Burgate in the county of Southampton.”

Another deed states that ” The said Robert White, Esq., having bargained and sold the Manor of Nuttingbarnes, with the appurtenances in the county of Middlesex, and the farm of Nuttyng-barnes, in the parish of Kensyngton, and the capital messuage with the appurtenances called Westbourne in the parish of Paddington, in the same county, and also the wood and lands called Nuttyngwood, Dorkyns Hernes, and Bulfre Grove, in the parish of Kensington, as also two messuages and tenements in Chelsaye, with all other the possessions of the said Robert White, in the same places and parishes ; and in consideration of £106 5s. 10d. had other lands conveyed to him by the King.”

It has usually been taken for granted that the young Whites were defrauded of their home in order that the land might be added to the royal park then being formed on the north side of London, but these preserves ” sacred to the King’s owne disport and pastime,” do not appear to have extended so far to the west. In any case there is no record that Henry VIII hunted or hawked in the thickets of Kellsal Greene or Nuttyngwood. And in 1547 he died.

The description of the estate as given in the deeds of 1543 is most valuable. The spelling of the name of the Manor, in the parish of Kensington, differs in the two documents. The Farm of Nuttyngbarnes no doubt stood ” in the midst of meadows surrounded by spacious barns and outhouses,” as it was standing in 1800, and continued to stand until about 1880). It is shown on most of the maps, see also the illustrations on page 10. Both Lysons, 1792, and Faulkner, 1820, definitely state that the farm and the Manor House were one and the same. The wood called Nuttyngwood covered St. John’s Hill, and seems to have extended in the shape of a wedge between Northlands and North Crofts down to the old Roman road. This area would account for the 200 acres of wood mentioned in 1526. A few elms, known from the rings of growth to be over 250 years old, have survived till recently in the garden to the south-west of the church, and fields called Middle Wood and North Wood once occupied part of the hill.

The lands called Dorkyns Hernes and Bulfre Grove are less easy to trace, but some information is obtained from two lists of the fields belonging to Chelsea Outland, dated respectively 1544 and 1557. These four pasture closes possessed the quaint names of Darkingby Johes or Darking Busshes, Holmefield, Balserfield and Baudelands. Probably a man named Dorking, pronounced Darking, had owned the land, for Dorkinghernes, or Dorkyns corner (Middle English ” herne ” or ” hurne,” a corner), lay to the west of Darking Busshes and seems to have covered the most northern part of Kensington parish. A meadow called Sunhawes (” haw,” a hedgerow) occupied the slope with a southern aspect and abutted on ” the close of Nottingbarnes.” Covering the site of Westbourne Park Station was arable land called ” Downes.” ” Bulfre Grove ” may have been named after some private owner. Possibly this ” land ” abutted on the Norlands Estate, for it is not mentioned in connection with the Chelsea fields.

The messuages on the estate were Westbourne Place and the Manor farmhouse. The cottages will be referred to later. The mills have not been traced.

In these deeds of exchange no mention is made of the ” 20 acres of moor, and 20 acres of furze and heath ” which existed on the estate in 1526. Even now the fringe of Wormwood Scrubbs invades the north-west corner of Kensington. Rough uncultivated land was unimportant as compared with ” 140 acres of meadow.” Reading this description there is no doubt that the bleating of large flocks of sheep and the merry shouts of haymakers resounded on the slope now occupied by gas-works and a vast array of tombstones. In the year of Henry VIII’s death ” the messuage called Westbourne with the land purchased of Robert White ” was demised to one Thomas Dolte, at a rental of one hundred shillings a year. Some connection with Knotting Barns was maintained, for the Parish Registers show that on February 27, 1614, the bodies of two tramps : ” William, a poore boy, name unknown ” and ” Dorothy Daggers,” both of whom died in Westbourne Barne, were brought to Kensington for burial.

The Chelsea fields were already in other hands.

In 1549 Edward VI granted the Manor of Knotting Barns to Sir William Paulet, Lord St. John of Basing, a man seventy-four years of age, but who, shortly after this date, became Lord High Treasurer and Marquis of Winchester : ” that gallant Lord Treasurer of whom Queen Elizabeth playfully declared that, but for his age, she would have found it in her heart to have him for a husband before any man in England.” He held the Manor for thirteen years, until in 1562 ” being indebted in sundry sums to her Majesty ” he surrendered this and certain other properties. Elizabeth then granted Knotting Barns to William Cecil, Secretary of State, created Baron of Burghley (Burleigh) in 1570, and Lord High Treasurer on the death of the aged Marquis in 1572. There seems to be no authenticated account of either of these Lord Treasurers having lived in North Kensington. But a curious letter exists, dated 1586, in which Lord Burleigh describes his interview with a group of officers who were searching scattered houses between St. John’s Wood and Harrow for the fugitive Anthony Babington and other conspirators in the plot to assassinate Queen Elizabeth and place Mary, Queen of Scots, on the throne. This interview may well have taken place at Lord Burleigh’s own farmstead of Knotting Barns. In any case the story proves that patches of forest remained, and that this part of the country was very secluded.

Lord Burleigh died in 1598. In March 1599 Sir Walter Cecil, Knight, as one of his trustees, sold the Manor for £2,000 to Walter Cope ” of the Strand.” But, as a debt on the estate was owing to Queen Elizabeth, a ” licence to alienate ” had to be obtained by Sir Thomas Cecil and Lady Dorothy, his wife, heirs of Lord Burleigh. Walter Cope also was obliged to pay £6 for a ” pardon.” This Walter, afterwards Sir Walter Cope, is a very important figure in local history. Between 1591 and 1610 he gained possession of almost the whole of the parish of Kensington, and built for himself the magnificent house first known as Cope’s Castle and afterwards as Holland House. But apparently he bought Notting Barns merely as a speculation, and, in November 1601, he sold it to Sir Henry Anderson for the sum of £3,400 ; this being a handsome profit on his expenditure of £2,006.

Sir Henry Anderson, Knight and Alderman, belonging to the Worshipful Company of Grocers, was Sheriff of London in the year 1601. He was a man of similar type to Robert Fenrother, though he was not so wealthy.Four years later he died leaving a son Richard, aged nineteen, as his heir.

In the Inquisition after the death of Henry Anderson, farms and a wood of 130 acres are mentioned, and the Manor was still held of the Crown by fealty and a rental of two or three pounds. ” A manservant ” died ” at Notting Barnes” in March 1603-4.. This death may have occurred during a visit of the family to their rural farmhouse. For, as there seem to be no entries relating to the Andersons in the Parish Registers, they cannot usually have made their abode in Kensington.

In 1675 a second Sir Richard Anderson was in possession, probably a son of the youth who succeeded to the estate in 1605.

These seventy years, beginning in the reign of James I and ending in that of Charles II, were years of stress and of great development in the life of the nation. At some time during this period the Manor of Knotting Barns ceased to belong to the Crown and became the property of the Andersons.

Yet, in 1672, when a Presentment of Homage was made by the tenants to the Lord of the Manor, the whole of the northern portion of the parish was included in Abbots Kensington, and Sir Richard appears as Freeholder of 400 acres. “ This,” writes Mr. Lloyd Sanders, “ is a curious illustration of the way in which the Great Rebellion had obliterated old memories.

Notting Hill is treated as if it formed an integral part of the Abbot’s Manor, which it never did, and among the freeholders appears Sir Richard Anderson, its owner. Possibly he did not care to assert manorial rights against his powerful neighbour at Holland House, who at that time was Robert Rich, Earl of Holland.”

With the Sir Richard Anderson of 1675 the olden times come to an end. For this reason the names of the known owners of the Manor down to the eighteenth century have been grouped together. From the beginning of the seventeenth century the population of Kensington increased rapidly.

About 1650 it became the custom to add the name of the district to the entry in the Parish Registers, and at once this “ Charter of the Poor Man,” as the Parish Registers have been called, provides information about the cottagers at Notting Barnes. Between 1650 and 1680 six young couples with the surnames of Brockards and “bronckard,” Ellis or Ells, King, Breteridge and Fell, brought infants to be “ baptised at the Font ” and some of the same children were buried in the churchyard. It must have been a risky proceeding to carry a baby of a few days old along muddy field paths all the way to Kensington Church.

Some delicate children were registered as baptised at home at “Noting-barns ” and also at “ Canselgreene ”; but it is quite evident that many births were not recorded. In the corresponding list of burials between the years 1654 and 1676 appear the names of Alse or Alice Welfare, Thomas Williams, Elizabeth Hihorne and Richard Whitte, each described as of Noting-barns, and Mary Davis, widow, who was buried from the house of Edward Fell. A pathetic little story can be built up round Daniel and Elissabeth King. An Elissabeth King, no doubt their baby daughter, died in I660. Her father died in the following year ;and after his death another little Elizabeth was born, who only survived for a few months. Then poor“ Widdo King ” took someone else’s baby into her desolate home, for a “ nurse child ” was buried from her cottage in 1663.

Just west of the detached portion of Chelsea, was a small collection of houses, the beginnings of the hamlet of Kensall or KellsellGreene.° These cottagers were chiefly “ parished in Wilsdon,” but in the middle of the seventeenth century four families are met with in the Registers of Kensington Church. Their names were Rippon, Shepparde, Cox and Beale. Each household possessed children, many of whom died in infancy. These families must have lived close to a crooked lane, the “ Way from Paddington to Harlestone ” (Harlesden). This ancient “ Horse Tract ” has become the Harrow Road, and forms the boundary between Kensington and Willesden. On the fields now covered by Kensal Green Cemetery there was a tenement with three acres of land, the freehold property in 1672 of a certain Widow Nichols. And at least one other little house stood on the south side of the boundary lane.

In the year 1820 Faulkner wrote,“ At Kensal Green is a very ancient public house, known by the name of the ‘ Plough,’ which has been built upwards of three hundred years ; the timber and joists being of oak, are still in good preservation.”

No doubt the oak joists came from the neighbouring woods. The “ Plough ” stands there yet, though,in the modern brick house at the junction of Ladbroke Grove and Harrow Road, there is little to remind the passer-by of the low-timbered building seen opposite,or the rustic charm of the more fanciful drawing on page 14. This wayside inn may go back as far as Faulkner suggests, for the Parish Registers show that “ Marget, a bastard childe, was borne in the Ploughe, and was baptised the 30th day of August, 1589-” A family named Ilford are said to have been landlords of the “ Plough ” for several generations.

It must be remembered that the information from the Parish Registers is over one hundred years later in date than the description of Knotting Barnes as given in the Deed of Exchange. After about 1680 there seems little to record for another hundred years of the northernmost part of the parish of Kensington.