| Peaceful hamlet | Notting Hill in Bygone Days by Florence Gladstone |

Notting Dale |

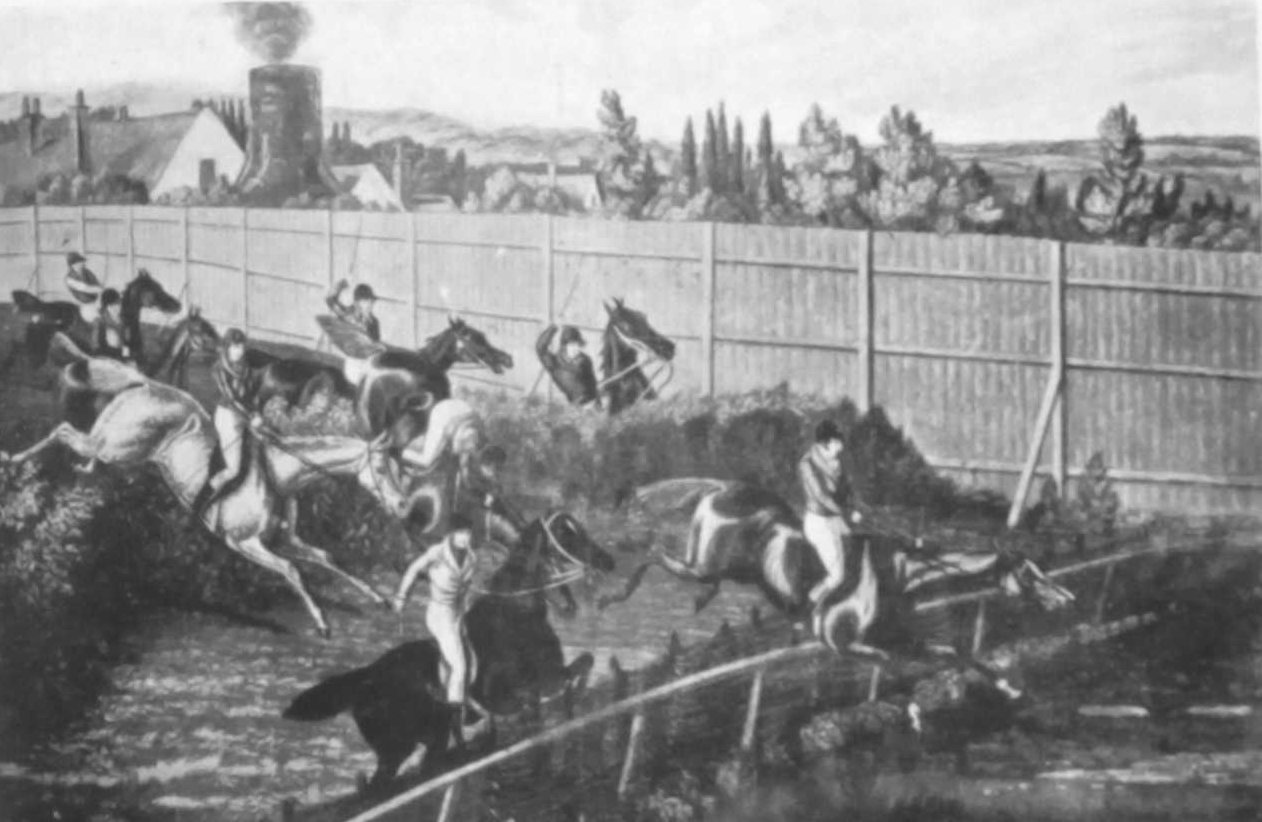

“In And Out” – from a series of prints of “The Last Grand Steeplechase” at the Hippodrome Racecourse, Kensington. 1841. By Henry Aiken Junior.

As buildings increase the story necessarily becomes more local. It is also impossible to avoid over-lapping of dates. This chapter begins with the time when Mr. John Whyte resigned the eastern half of the Hippodrome with the footpath over the hill, and Mr. James Weller Ladbroke, the ground landlord, let this piece of land to a Mr. Jacob Connop. The date of this transaction was October 5, 1840. The plan, originally attached to the deed,’ has already been mentioned as giving the names of fields. Mr. Connop no doubt had advanced money to Mr. Whyte, for, besides taking part of the race-course off his hands, Mr. Connop became ” proprietor ” of the race-course, when, in May 1842, the announcement was made that the land had been taken possession of by mortagees for building purposes. Already, before the Hippodrome was closed, Messrs Connop and Duncan had started building operations. Kensington Park Villas, a terrace of small houses near the public entrance, houses now incorporated into Kensington Park Road, were amongst the earliest to be built. By 1844 six large detached houses higher up the new road, the Swiss Villa, now No. 48, and its companions, the Italian, the Norman, the Elizabethan, etc., were in course of construction. The plans for these beautiful villas were exhibited at the Royal Academy. A row of houses was also commenced to face “Mr. Ladbroke’s common garden,” these being No. 20 and Nos. 23 to 47, Ladbroke Square. Perhaps the suburb was too remote from London for such large houses to be let readily. Whatever the reason, in February and again in May 1845, Mr. Jacob Connop appeared before the Insolvent Debtor’s Court, and ” an assignee was appointed to carry the works to a conclusion.” The liabilities of Messrs’ Connop and Duncan were then stated to be between £60,000 and £70,000. The original area of the Hippodrome having reverted to the ground landlord, Mr. J. W. Ladbroke, he entrusted the planning of the whole estate to Mr. Thomas Allom, architectural artist. ” Kensington Park ” was chosen as the name, and it was stipulated that houses put up by purchasers of building plots should be in accordance with the general scheme. A large and elaborate plan of Kensington Park Estate is given in E. Daw’s map of Kensington, 1846, a copy of which may be seen at the Public Library, but that shown on Wyld’s map of 1850, on page 120, is sufficiently clear. A comparison with the more modern conditions shown in the map on page xiv, and all maps after 1850 proves that much of the original design has been carried out, and, indeed, in the southern half of the estate the resemblance is remarkably close. A wide tree-lined avenue, now Ladbroke Grove, cuts through a series of roads curving round the hill, the culminating point being a House of God. As first planned these roads were confined within the limits of the estate, but this part of the scheme was altered, and the crescents were extended to the east across Portobello Lane, thus forming a connection with building which was in progress in Bayswater and the nearer parts of Paddington. In the northern half, instead of detached and semi-detached villas, solid rows of houses were built. But the western border remained self-contained, and between Clarendon Road and Notting Dale there is a group of blind alleys which are a source of annoyance to the present day. On the south Mr. Ladbroke had set aside nearly seven acres to form a pleasure ground, the largest common garden in London, and a road along the side of the square, called Ladbroke Road until that name was given to Weller Street, connected Kensington Park Villas with Ladbroke Terrace and Ladbroke Place. Another large space, which was to be called either Beaufort or Lansdowne Square, was afterwards cut across by the houses of Stanley Gardens. Up to this period there had been no church in the parish of Kensington north of the main road.

Mr. Robert Roy, of Messrs. Blunt, Roy and Johnson, purchased and presented a site on the top of the “Hill for Pedestrians ” for an Early English stone church, designed by Messrs. Stevens and Alexander, to accommodate fifteen hundred worshippers. The builder was Mr. Hicks. As too much stone and brick had been estimated for, the Vicarage and the adjoining house were built of the extra stone and Nos. 3 and 4, Ladbroke Mount, now Lansdowne Crescent, of the extra brick. At first ” St. John the Evangelist ” stood alone ” in the hay-fields.” See pictures on page 124, and 166. When viewed from Crescent Street or from Ladbroke Grove the church now is embedded among trees on the hill-top. Although ” erected before Gothic details were fully understood . . . it is one of the best situated and best designed churches in the parish.” St. John’s was consecrated on January 29, 1845, six months before the smaller church of St. James’s Norland. The parochial districts given to these two churches included the whole area of Notting Hill : one parish extended from the top of Campden Hill to Kensal Green, the other parish covered Norland Town. The first incumbent of St. John’s, the Rev. William Holdsworth, 1845 to 1853, was succeeded by the Rev. E. Proctor Dennis who died of cholera in 1854, but from 1855 to 1878 the Rev. John Philip Gell presided over the parish. (Mrs. Gell was the only child of Sir John Franklin ; this fact accounts for the vertebrae of an Arctic whale which lay for many years in the Vicarage garden.) Mr. Gell was followed by the Rev. Crauford Tait, whose lamented death took place three months after his institution. (It is said that the double gates leading to the Vicarage were made so that the archiepiscopal carriage might drive in.) The houses built before 1850 are clearly marked in the map on page 120. Upper Lansdowne Terrace, now Nos. 67-77, Ladbroke Grove, occupies the actual summit of the hill ninety-nine feet above sea-level. It has been asserted that the hill-top was originally somewhat further to the south, and that it was reduced by ten feet in order to level the road facing the church : Kensington Park Gardens. This seems unlikely. When first built the view from Upper Lansdowne Terrace must have differed little from that described by Thomas Faulkner •in 1820. At the present time ” from the housetops a splendid panorama may be enjoyed up the Thames Valley . . . as far, on a clear day, as Windsor Castle . . . while Citywards, one may discern St. Paul’s Cathedral and Westminster Abbey.” The chief names of these early roads are Ladbroke, which explains itself, Clarendon, probably from the Earl of Clarendon who figured in the Crimean War, and Lansdowne, either from the noted politician of that name, or because the Dowager Marchioness of Lansdowne, Mistress of the Robes to Queen Victoria at the commencement of her reign, was then living on the summit of Campden Hill. Upper Lansdowne Terrace was faced by a row of houses called Stanley Villas, now Nos. 42 to 58, Ladbroke Grove ; 42 and 44, Ladbroke Grove was a single house with a central tower. There is a tradition, probably inaccurate, that this house was built by Mr. Ladbroke for his own use and was called the Manor House. It is also said that, when King Edward VII was a child, his parents were recommended by their physician to send him to Notting Hill for the benefit of his health, and that one of these villas was prepared for him but was not used. Another version relates that the then Prince of Wales, when about nine years of age, spent some months in the Manor House under the care of a medical man. The story gains some degree of probability from the fact that Sir James Clarke, the well-known physician who advised Queen Victoria to go to the neighbourhood of Braemar, recommended Ladbroke Square as the healthiest place in London to another patient who consulted him on where to take a house. This lady bought Hanover Lodge, Hanover Terrace, built in 1837 or 1839, and her descendants have lived there ever since. The Hippodrome enclosure, as already stated, covered nearly 200 acres of land. A large part of the central portion known as the Hundred Acre Estate was bought from Mr. Ladbroke by Mr. Charles Henry Blake, whose descendants still hold property in the district. It was to Mr. Blake that Mr. Thomas Allom dedicated the fine litho-graphic view of Kensington Park Gardens, shown on page 128. Sixteen houses in the Gardens are due to Mr. Blake, and were sold by him to Mr. George Dodd in 1859 and 1860. The earliest houses in Kensington Park Gardens were numbers 1, 2, 3, 5, and 8. These were erected by Mr. William Henry Drew, who also built and owned houses in Ladbroke Road and Ladbroke Terrace. Mr. Drew parted with his houses in Kensington Park Gardens in 1859-1860, and many other houses changed hands about that time. By 1858 the remaining houses of Ladbroke Square (see page 112), and the houses on both sides of Kensington Park Gardens were inhabited. Much of the actual building of the roads between Notting Hill Gate and Arundel Gardens was carried out by Mr. John Dewdney Cowland and Mr. William Wheeler. The site of Mr. Wheeler’s own house and grounds is partly covered by Victoria Gardens, Ladbroke Road.

In November 1855, ten years after St. John’s Church was opened, the foundation stone of St. Peter’s, Bayswater, was laid. The church was consecrated in January 1857. St. Peter’s is ” an Italian basilica with a good colonnade of the Corinthian order.” Mr. Thomas Allom made designs for this church, but the architect appears to have been ” Mr. Hallam, a young practitioner of great promise who died early.” The tower over the facade groups well with the surrounding houses (see illustration on page 166), and when viewed from the hollow in Portobello Road is said to resemble a scene in Portugal. The original ground plan was a parallelogram, with the present galleries extending to the east wall in which were three windows. Two of these windows have been placed in the west gallery. In 1878 it was decided to construct a chancel and apse, but the year 1887 had arrived before the ” noble apsidal sanctuary ” was completed, chiefly from the designs of Sir Charles Barry. On the south wall of the nave is a marble memorial to the wife of the first rector, the Rev. F. H. Addams. She died in 1 86o while nursing her five children with scarlet fever. (The ravages of scarlet fever was a tragedy which occurred in other houses in the district at this period, for extraordinarily little was known about the spread of infectious disease.) It is not, however, the first rector, but the Rev. John Robbins, D.D., who held the living from 1862 to 1883, whose personality is best remembered in connection with the earlier history of St. Peter’s. Among the first purchasers of land on the Hippo-drome Estate was the Rev. Samuel Edmund Walker, of St. Columb Major in North Cornwall, who appeared in Notting Hill with the intention, so it was believed, of investing half a million sterling in house property. ” He was not long in causing hundreds of carcases of houses to be built. If he had commenced his operations on the London side of the estate no doubt the houses would have been sold and a fine investment made, but as he preferred building from Clarendon Road (where roads were not made) towards London the land was covered with unfinished houses which continued in a ruinous condition for years, and the consequence was the investor was almost ruined.” The Old Inhabitant, perhaps here combines the work of various speculative builders, but it will be seen later on that Dr. Walker’s scheme was of huge proportions. The history of two houses in Clarendon Road may be taken as typical of many others. No. 12, Clarendon Road has a charming long garden, and is still very countrified, but the ground floor is better built and is altogether superior to the upper stories. Mr. Hugh Carter, the artist, bought the house in 1866 from Mr. Henry Drew, who had taken it over as bankrupt property. A photographer was the first tenant. No. 38, originally known as 28, Clarendon Road Villas, is one of eight well-designed detached villa residences facing west. There is reason for thinking that these houses were begun by the Rev. Dr. Walker, and were left in an unfinished state. In 1846, No. 38, Clarendon Road was handed over by James W. Ladbroke to Mr. Richard Roy, but he soon gave up possession. The close proximity of the ” Piggeries and Potteries ” was a sufficient reason why the western parts of the estate did not take the public fancy. Even in 1867, Mr. Lionel Clarke and other householders in Lansdowne Road were obliged to complain to the vestry of the boiling down of fat at an hour in the night when it was fondly hoped that the smell would not be noticed. Fortunes were certainly made, but fortunes were also lost in developing Kensington Park, and ” sad tales could be told of not a few who sank their all in bricks and mortar. Lawyers and moneylenders have in time past reaped a rich harvest at Notting Hill, but many a hard-working man, falling into their hands, has been ruined ” (see note 6). The failure of Overend and Gurney’s Bank in 1866 seems to have dealt a crushing blow to the estate. Few of the builders survived the ordeal, and of those few the ” efforts were maimed ” (see note 4). Even such an influential man as Mr. Drew became involved in mortgages, and some of Mr. Felix Ladbroke’s ventures are believed to have been costly failures.

The Hundred Acre Estate got into liquidation. The mortgage of part of it was then taken over by Richard Roy, Esq., already mentioned. (Rents charged for the use of some of the common gardens are still paid to the firm of Messrs. Roy and Cartwright.) Many persons, when recalling early impressions, refer to houses without roofs, or with holes for windows, black holes which seemed like staring eyes to the frightened child who hurried by. The row of unfinished carcases on the north side of Ladbroke Gardens came into the hands of Mr. Andrew Perston of 9, Kensington Park Gardens, and his sister-in-law, Miss Churchill, and a young architect, now Sir Aston Webb, P.R.A., put staircases into some of these houses. Other instances could be given ; but enough has been said to explain the mongrel condition of much of the building, especially on the fringes of the Hundred Acre Estate, and the large number of ” made-down ” houses which have always puzzled visitors to the locality.

Shortly after the Hippodrome was given up a row of small two-storied houses was built at the south end of Portobello Lane overlooking the garden of Elm Lodge. These houses were long known as Albert Place, but are now part of Pembridge Road. Most of them have been converted into shops, but they retain an old-world air, and two or three are in their original condition, at least, externally. In one of these little houses, then No. 18, Notting Hill, Feargus O’Connor, the ” Lion of Freedom,” spent the last clouded days of his stormy public life. He it was who, on April 10, 1848, had commanded the vast assemblage of Chartists at Kennington Common, when troops under the Duke of Wellington were called out to quell the rioters. Feargus O’Connor died August 30, 1855. On September 11th, a great body of his followers marched from Notting Hill Gate to Kensal Green Cemetery, where a funeral oration was delivered by Mr. Edward Jones. The grave is marked by an obelisk. In 1849 Horbury Chapel and school were placed at the junction of Ladbroke and Kensington Park Roads. With Norman towers flanking the façade, the chapel stands in a commanding position, indeed this corner is one of the most effective points in the whole neighbourhocd. See illustration on page 166. ” Horbury ” was a ” hiving off ” from the crowded congregation at Hornton Street, Kensington, but a close connection was maintained with the parent church. The name is that of a village in Yorkshire, the birthplace of Mr. Walker, deacon and treasurer, to whom the success of the undertaking was largely due. During the ministry of the Rev. William Roberts, the beloved pastor from 1850 to 1893, ” Horbury ” was the centre of much congregational life.8 For awhile it was also the meeting place of the Kensington Parliament, a debating society which developed the powers of several well-known public men. The buildings on the north slope of St. John’s Hill are all of later date, though one row of small houses called Kensington Park Terrace was built in Kensing-ton Park Road as early as 1853. The name and the date may still be seen on the pediment facing Arundel Gardens. In 1862 a Proprietary Chapel was placed a little lower down the hill. This iron building belonged to an Independent minister, known as Mr. Marchmont. He was an eloquent preacher and attracted large crowds. Services were conducted according to the form of the Church of England ” to the great scandal of the neighbourhood.” One Sunday night in May 1867 a fire took place, and the building was gutted. Ugly reports spread as to the cause of the conflagration. A large brick church was soon commenced by Mr. Marchmont on the same site, but the Bishop of London intervened. In 1872 this ” carcase ” was purchased by a body of Presbyterians who, for two or three years, had been worshipping in the Mall Hall, Notting Hill Gate. Peculiarities in the internal arrangements of Trinity Presbyterian Church were due to its origin. This church had a series of remarkable pastors, among whom may be mentioned the first minister, Dr. Adolf Saphir, noted fcr his wonderful knowledge of the Bible, Dr. Sinclair Paterson, and the saintly Rev. J. H. C. MacGregor.

A very undesirable music palace, called Kensington Hall, stood on the spot where is now the Kensington Presbyterian Hall, and somewhat further down the road was the Mission Room belonging to All Saint’s Church. (The site is occupied by the Notting Hill Synagogue, founded by Mr. Moses Davis to meet the needs of a large community of Jews, chiefly Russian and Polish, who have come to live in the immediate neighbourhood.) In 1867 a charming terrace of small houses was built in Blenheim Crescent originally called Sussex Road ; these houses were on the edge of the country, and the scent of new-mown hay used to be wafted in at the windows across the garden of the Convent. This Franciscan Convent of the Order of St. Clare was connected with St. Mary of the Angels, Westmoreland Road, Bayswater. It was founded by Cardinal, then Father, Manning, and had been placed in 1859 on low ground at the foot of the hill, where formerly withy beds showed the course of the stream running west from Portobello Lane. The Convent buildings and the large garden in Ladbroke Grove cover one and three-quarter acres ; about thirty nuns are said to live within the high, encircling wall.

Immediately to the north of the Convent stood a country inn with a skittle alley beside it. The ” Lord Elgin ” is still remembered by many local inhabitants. It is now represented by the Elgin Tavern at the corner of Ladbroke Grove and Cornwall Road. In 1863 a modern Gothic church with bands of brick and stone, flying buttresses and a spire, was planted down in the midst of fields on the west side of Ladbroke Grove opposite the Convent wall. The site for ” St. Mark’s in the Fields ” had been given by Mr. Charles Henry Blake, and Miss E. F. Kaye presented her nephew to the living. The Rev. Edward Kaye Kendall, formerly curate at St. John’s, was ” an enlightened and able minister,” and St. Mark’s became the centre of valuable parochial organizations, including an excellent National School. Where the Parish Hall now stands was then an allotment. In 1871, the average congregation numbered over one thousand persons belonging both to ” the higher middle class and the poor.” Many beautiful additions have since been made to this church, and three galleries have been removed. Before the completion of the church a Baptist chapel had been placed close by. Few people know of the quaint origin of the chapel in Cornwall Road. In 1862 Sir Morton Peto obtained a contract for the removal of the buildings of the Great International Exhibition in South Kensington, and he was presented by Messrs Lucas and Co. with the end of one of the transepts. This transept, ” a long wooden and plaster object ” was ” stuck up ” at Sir Morton Peto’s expense as Ladbroke Grove Baptist Church. Later on it was entirely rebuilt. In spite of its shoddy origin this chapel ” has been honoured by the ministry of several notable men,” the first minister being the Rev. James A. Spurgeon, 1863 to 1867, brother of the renowned Charles Spurgeon. The advance of buildings is indicated by the dates of these various places of worship. Before the days of the chapel in Cornwall Road, a boxing booth stood on this spot, run by the noted prize-fighters, Tom King and Jem Mace. Tom Sayers and another prize-fighter owned a circus which occupied the corner of Ladbroke Grove and Lancaster Road. The gardens behind Lancaster Road mark the boundary of the Hippodrome Estate. Kensington Park Hotel, No. 139, Ladbroke Grove, which is shown in the photograph of 1866, on page 184, is beyond the limits, as is also Lancaster Road. Of late years Lancaster Road has become the centre of an interesting group of philanthropic agencies including the Campden Technical Institute, a modern development of the Campden Charities, the Romanesque Church of St. Columb, originally a daughter church of All Saint’s, and the fine red-brick building of the North Kensington Branch of the Public Library. Although this building only dates from 1891, the Notting Hill Free Library, from which it has sprung, was started in the year 1874 at No. lo6, High Street, Notting Hill Gate, through the private exertions of Mr. James Heywood of 26, Kensington Palace Gardens. Mr. Herbert Jones, librarian-in-chief, was appointed as assistant to Miss Isabella Stamp (a lady with the regulation ringlets of the period) who presided over this library at Notting Hill Gate. After Mr. Heywood’s death it was carried on for a while under the Public Libraries Act, by a committee of local gentlemen. The corner of Ladbroke Grove and Lancaster Road may be looked upon as the central point of North Kensington. Unfortunately a group of mean streets extends from Cornwall Road to Clarendon Road. Hanover Court, the strange circle of houses with radiating gardens which fills up the north-west corner of the original plan (see map on page 12o), has been replaced by a veritable slum area. It must be remembered however that the houses were not built for the class of people who now inhabit them.

Before leaving the subject of Kensington Park a little more may be said about the development of the portion on the top of St. John’s Hill. When Ladbroke Square was laid out Mr. J. W. Ladbroke arranged for a rent charge of three guineas per annum on each house over which he had jurisdiction. This was for the upkeep of the garden. Other houses within the radius of half-a-mile, on paying a rent, were allowed the use of the common pleasure ground. Mr. James Weller Ladbroke died in 1847. In 1864 his cousin, Mr. Felix Ladbroke, parted with his interest in the Square garden for the sum of £2000, raised by a hundred shares of £20 each. Six trustees and a garden committee of five persons, living within a hundred yards of the Square, were appointed from among the shareholders to collect and employ the rent charges and subscriptions in order that the garden or pleasure ground, the fences, gates and gardener’s lodge, the summer houses, furniture and property might be kept up in perpetuity. Surplus funds were to be divided among the shareholders. These provisions are still carried out. The original trustees were Edward Langdon Brown, M.R.C.P., William Matthewson Hindmarsh, Q.C., an authority on Patent Law ; Arthur Pittar, a diamond merchant (who in 186o had taken No. 4, Kensington Park Gardens, the house formerly kept by Miss Killick and Mrs. Lewis as a boarding school for young ladies) ; and Alfred Waddilove, D.C.L., a probate lawyer, all living in Kensington Park Gardens ; also Robert Cocks of Wilby House, Ladbroke Terrace, a music publisher, and Henry Liggans of Ladbroke Square, author of a pro-slavery pamphlet. The solicitor of the company was Edward Young Western, whose father owned houses in Kensington Park Gardens and in Ladbroke Square. The firm still remains solicitors to the trust. The deed of conveyance, dated March 1, 1864, and the schedules attached to it throw further light on the earliest inhabitants, but it is not possible to tell who had any particular house. Much interesting information on the subject was furnished to the writer by Mr. Lionel A. Clarke, a former Master of the Supreme Court, who in 1916 was living at No. 5, Ladbroke Square, the house occupied before his time by the blind William Gardner, whose name will always be remembered with gratitude for his benefactions to those afflicted in like manner with himself. Evidently in 1864 men of position and intelligence were living on the breezy heights of Notting Hill, and merchants, lawyers, men of science, literary men and artists have continued to inhabit these comfortable mid-Victorian houses to the present day. In the words of a modern writer : ” Leafy Ladbroke has a peculiar completeness as a quarter . . . and it gives me a stronger impression of social stability than any other part of London that I know.” But whilst it may be admitted that the bulk of the dwellers in Leafy Ladbroke have been those ” solid men, the backbone of the country ” upon whom ” the greatness of England is founded,” men whose business it is to buy something and sell it again at a profit, it is also true that the lump has been leavened by an admixture of less self-centred elements : men and women who have devoted their energies to furthering the welfare of their neighbours. The following lines from ” An Evening Song,” by Henry S. Leigh,H belong to the period which has been described.

Fades into twilight the last golden gleam Thrown by the sunset on upland and stream ; Glints o’er the Serpentine—tips Notting Hill—Dies on the summit of proud Pentonville. Day brought us trouble, but Night brings us peace ; Morning brought sorrow, but Eve bids it cease. Gaslight and Gaiety beam for a while ; Pleasure and Paraffin lend us a smile.

Temples of Mammon are voiceless again—Lonely policemen inherit Mark Lane—Silent is Lothbury—quiet Comhill– Babel of Commerce, thine echoes are still.

• • • •

Westward the stream of Humanity glides ;—’Buses are proud of their dozen insides, Put up the shutters, grim Care, for to-day—Mirth and the lamplighter hurry this way.

These light-hearted verses show how times have changed within living memory. The strain and stress of modern conditions in ” Uxbridge Road,” are described in a most beautiful poem by Evelyn Under-hill, from which some lines are quoted:—

The Western Road goes streaming out to seek the cleanly wild, It pours the city’s dim desires towards the undefiled.

The torments of that seething tide who is there that can sec ? There’s one who walked with starry feet the western road by me !

He is the Drover of the soul ; he leads the flock of men, All wistful on that weary track, and brings them back again.

He drives them east, he drives them west, between the dark and light ; He pastures them in city pens, he leads them home at night.